The past year has brought an unprecedented change in the way Americans work, with millions of workers working from home and connecting to colleagues and clients virtually. In an AESG report titled “Internet Access and its Implications for Productivity, Inequality, and Resilience,” economists Jose Maria Barrero (Instituto Tecnológico Autónomo de México), Nicholas Bloom (Stanford University), and Steven J. Davis (University of Chicago) examine the role that home internet quality plays in driving worker productivity under this new work paradigm.

The authors draw timely insights and lessons from the Survey of Working Arrangements and Attitudes (SWAA), an original cross-sectional survey they have collected since May 2020 on over 40,000 working age Americans. They estimate that universal internet access – defined as high quality, fully reliable home internet service for all Americans – would raise earnings-weighted productivity in the post-pandemic economy by 1.1%, which implies flow GDP gains of $160 billion per year, or a present value gain of $4 trillion at a 4% discount rate. They estimate that universal access would raise the extent of work from home (WFH) in the post-pandemic economy by about seven-tenths of a percentage point.

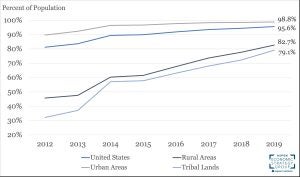

Universal internet access promotes economic and social resilience by facilitating commerce and socialization at a distance. Internet technologies enabled large sectors of the economy to function well during the pandemic. In addition, existing evidence suggests that home internet access may help to mitigate the negative health effects of loneliness and social isolation in a time of pervasive social distancing.

THE SURVEY OF WORKING ARRANGEMENTS AND ATTITUDES

Barrero, Bloom, and Davis have fielded the Survey of Working Arrangements and Attitudes since May 2020, collecting 2,500 to 5,000 responses per month. Survey respondents report higher productivity when working from home during the pandemic as compared to when working on employer premises before the pandemic.

In previous research, the authors combined this survey data with information about employer plans regarding post-pandemic work arrangements to predict what a re-optimization of work arrangements post-pandemic would look like. They estimated that one-fifth of paid workdays will be supplied from home in the post-pandemic economy and more than a quarter of workdays on an earnings-weighted basis. They also estimate that re-optimization could be expected to boost productivity by close to 5%, largely through saved commuting time.

PROJECTING THE PRODUCTIVITY EFFECTS OF UNIVERSAL ACCESS

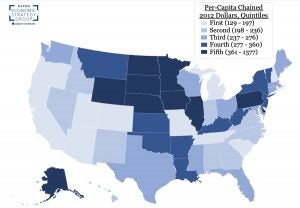

The authors combine individual-level data on the planned extent of WFH in the post-pandemic economy with individual-level estimates for the productivity impact of universal access to project the effects of a hypothetical move from the current state of internet access to one with high quality, fully reliable internet access in all households. The authors find large productivity consequences as a result of imperfect internet: a 3% aggregate labor productivity shortfall during the pandemic and a 1.1% gain from universal access in the post-pandemic economy. To the extent that better internet access improves WFH efficiency, the authors conclude that the overall estimated impact on the extent of WFH—an increase of 0.7 percentage points—is quite modest both during and after COVID. Importantly, the impact also varies little across demographic groups.

Barrero, Bloom, and Davis also derive implications for aggregate output, finding that the flow output loss during the pandemic is nearly three times as large as the projected flow benefits from universal access in the post-COVID economy. They note that this comparison underscores the economic resilience value of universal access: the output payoff is much larger in pandemic-like disaster states when output is unusually low and the marginal value of output is unusually high.

Barrero, Bloom, and Davis additionally analyze the earnings gains to workers from the associated productivity enhancements and estimate that such gains would be nearly uniform across income and demographic groups, meaning that productivity improvements would not come at the expense of widening inequality.

The authors recognize that there is uncertainty around their estimates of the impact of universal access on productivity and output. For instance, insofar as pandemic-related stressors (kids at home, lack of technological familiarity) pulled down WFH productivity during the pandemic, their estimates might understate the positive effect of internet access on WFH productivity after the pandemic. In addition, they lack survey data on the relative efficiency of WFH for respondents with no WFH experience during the survey period, accounting for 43.3% of respondents on an equal-weighted basis and an estimated 34.2% on an earnings-weighted basis. The lack of data for these respondents may lead them to overstate the effects of universal access.

INTERNET ACCESS AND SUBJECTIVE WELL-BEING DURING THE PANDEMIC

The authors examine the social effects of fully reliable internet access, particularly during crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic. They cite evidence that suggests that social distancing during the pandemic and pandemic-related stresses had negative health effects for many Americans. Such evidence motivates the hypothesis that better internet access during the pandemic alleviated the harmful psychological and other health effects of social distancing and pandemic- related stresses.

Using responses from the SWAA, the authors conclude that universal access would materially improve well-being during pandemic-like disasters for persons who currently lack home internet service while smaller improvements in well-being would accrue to persons who currently have subpar access.

UNIVERSAL ACCESS AS A SOURCE OF RESILIENCE

Barrero, Bloom, and Davis emphasize that by raising output in the face of infectious disease outbreaks, biological attacks, and other disaster states that involve physical distancing, universal access to high-quality home internet service would strengthen U.S. economic resilience. For society as a whole and for individual firms and workers, the capacity to quickly switch between production modes of roughly equal productivity is a valuable option that pays off especially in bad states of the world. The authors’ analysis suggests that the output payoff to universal access during pandemic-like disasters is nearly three times as large as the payoff during normal periods and that universal access promotes resilience by providing a ready means of engagement and socializing when circumstances compel physical distancing.

The authors also cite other important benefits of universal access that they do not quantify, such as the ability of households to turn to online shopping and home delivery services during a pandemic-like disaster, increased compliance with stay-at-home orders, and ameliorated gaps in remote learning opportunities. The authors underscore the importance of such enhanced economic and social resilience in the face of recurring outbreaks of COVID-19 and other infectious diseases.

Suggested Citation: Barrero, Jose Maria, Nicholas Bloom, and Steven J. Davis. December 10, 2021. “Internet Access and Its Implications for Productivity, Inequality, and Resilience”. In Rebuilding the Post-Pandemic Economy, edited by Melissa S. Kearney and Amy Ganz. Washington, DC: Aspen Institute, 2021. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14057577.

Chapter

Executive Summary