The Economics of Medicare for All

SUMMARY:

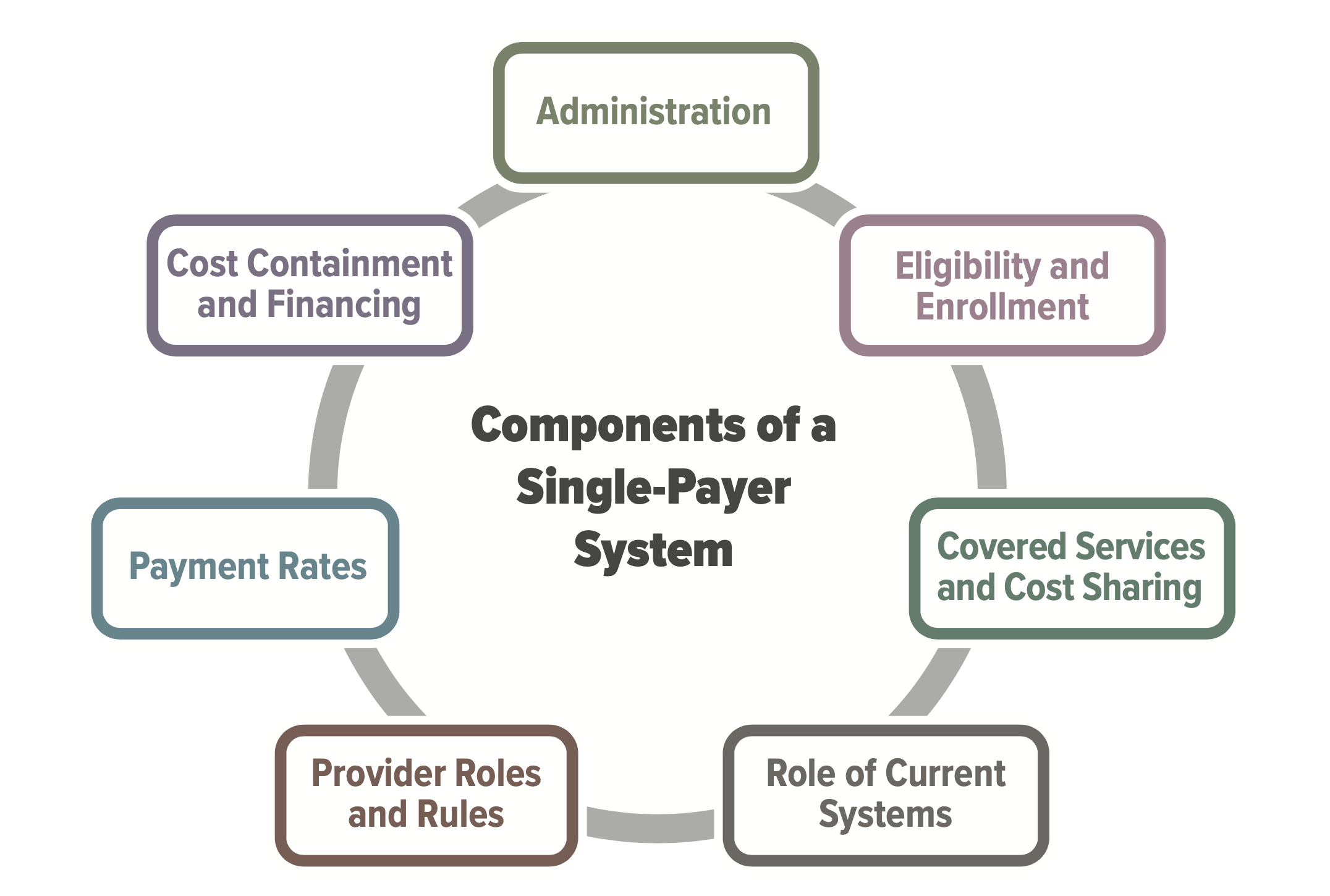

Policymakers and political candidates are expressing renewed interest in expanding the role of government in increasing access to and affordability of health care for all Americans. The most prominent proposal, Medicare For All, is supported in some form and under varying definitions by the majority of 2020 Democratic presidential candidates, and would create a single-payer healthcare system funded by the U.S. federal government.

Garthwaite argues that the current public debate about Medicare For All fails to take into account the likely consequences that such a large change to the health-care system would bring about. For example, if such a system adopted the existing Medicare price schedule, the average quality of health services would likely decline. A single-payer system would, by definition, make the U.S. government a monopsonist in the health-care labor market, allowing it the option to exert downward pressure on wages which could impact the availability of healthcare services and the supply of labor. In the market for prescription drugs, a U.S. single-payer could exert its buying power to lower drug prices but doing so would likely reduce innovation in that sector and reduce access to treatments.

Garthwaite also discusses alternative policy reforms that could promote affordability and access in the current U.S. health-care system, centered around introducing more competition to healthcare markets and making Medicare more efficient.

KEY POINTS:

- High health-care costs remain a barrier to universal coverage, with roughly 10% of Americans still uninsured. Medicare For All would reduce costs by reducing administrative costs and expanding price regulation.

- Medicare For All would only successfully reduce drug prices if it reduced treatment options for enrollees. Monopsony power exists when a buyer has the option of “walking away” from a negotiation – Medicare Part B, which is required to buy nearly all drugs needed by enrollees, does not have this option.

- Medicare For All would likely remove incentives for hospitals to invest in improving the quality of their care. Currently, a significant driver of a hospital’s incentive to invest in better care is driven by the competition motive – consumers will go to the hospital with the best care, allowing that hospital to negotiate a better deal with insurers. Medicare, on the other hand, pays hospitals based on an estimate of the costs of the average hospital. Replacing the competition motive would therefore lead to substantial decreases in quality of care.

- 60% of US health care spending goes to labor costs. Any meaningful effort to reduce costs would likely rely on reducing health workers’ wages, which would impact the supply of workers in health-care industry.

- The establishment of price ceilings for drugs would reduce prices for treatments that currently exist while removing the incentive for pharmaceutical manufacturers to invest in researching new treatments. Pharmaceutical markets are global, and manufacturers often undergo the massive upfront investment required to research a new drug because of expected returns from US sales. Because the United States accounts for a larger share of the global market, its pricing decisions have far more influence on the pace of development of future products.

AUTHOR RECOMMENDATIONS:

There are various means by which competition can be introduced to healthcare markets to bring down costs without sacrificing quality of care.

- There are multiple avenues available to introduce competition to healthcare markets. These include granting generics manufacturers full access to samples of brand-name drugs once the patent protection period has ended. In markets that are too small for more than one competitor, a request-for-proposal (RFP) process should be implemented, with manufacturers charging a fixed percentage above manufacturing costs.

- Medicare can and should be reformed to introduce competition and eliminate perverse incentives. Medicare Part B, for example, should use vendors to negotiate drug prices, rather than paying doctors a fixed margin above the price of the drug they prescribe. The reinsurance program of Medicare Part D, meanwhile, should be reformed so that private insurance companies – and not Medicare – are responsible for covering the majority of “catastrophic coverage” treatments. Such reforms, among others, would likely increase incentives to negotiate prices, increase competitive pressures, and decrease health care costs.