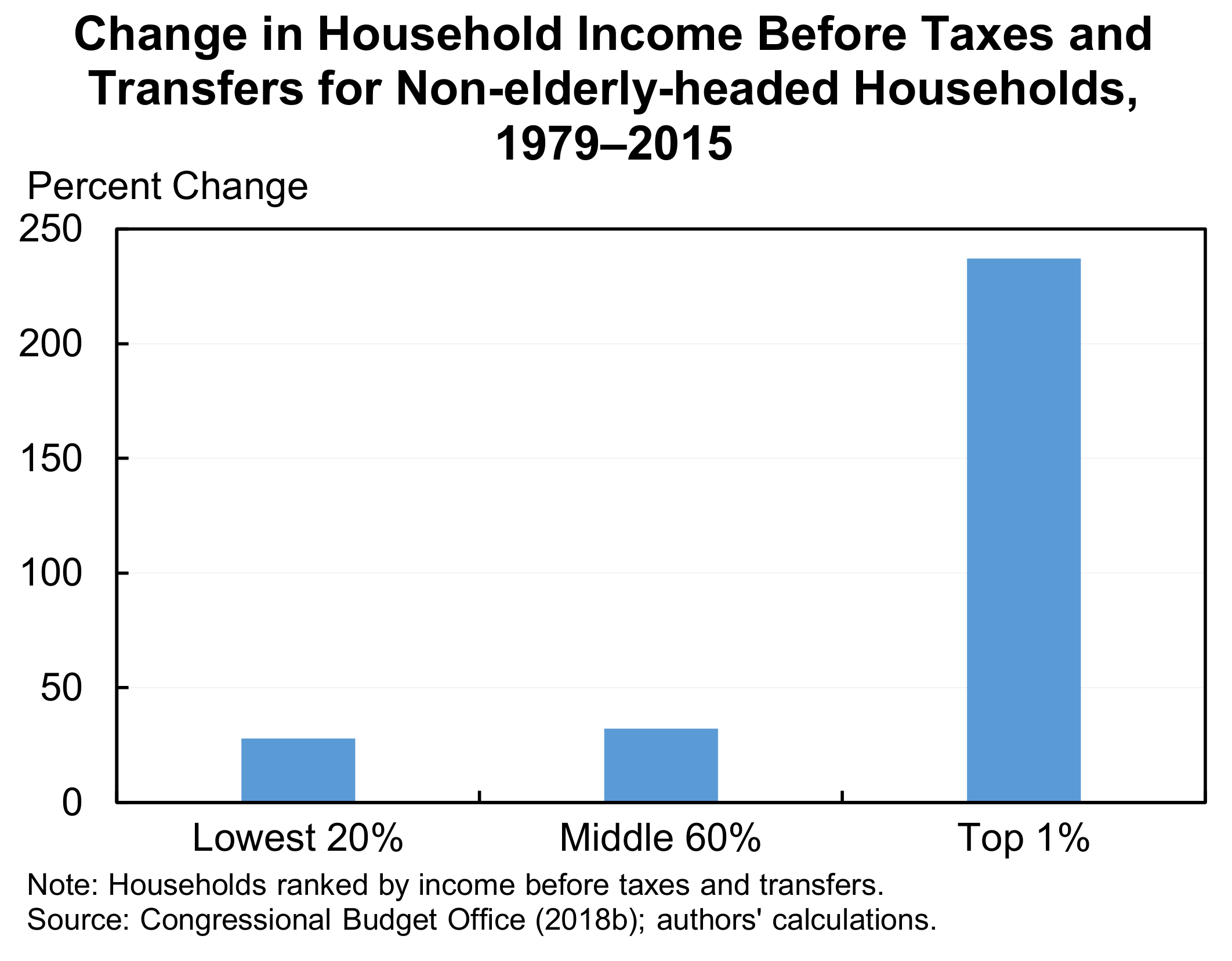

Many Americans are being left behind by today’s modern, global economy, and they are justifiably angry about it. Growing numbers of people feel our economic and political systems are rigged against them. And it’s no wonder why.

Recent progress in low- and middle-income wage growth is a blip against decades of wage stagnation. Low unemployment masks the fact that millions of prime-age men and women are missing from the workforce altogether. Today’s adults are less likely to earn as much as their parents did, and they foresee the same fate for their own children.

Concrete economic policy solutions are urgently needed. But the hollowing out of America’s middle class has coincided with the disintegration of our political center and the weakening of the very political institutions that sustain our democratic policymaking process. No issue underscores this breakdown more than the historically long government shutdown our country just suffered.

We must turn these tides.

Our experiences in public service have taught us that policymaking among parties that passionately disagree is never easy, but it is made possible through adherence to certain principles of good governance.

First among them is a commitment to truth, which must be rooted in rigorous analysis. There can simply be no good policymaking without first establishing a common set of facts about what is happening in the world and what any given policy or proposal will likely accomplish.

Second, good policymaking requires that lawmakers trust one another. This takes time, the ability to convene in confidence and a mutual commitment to shared goals. This is precisely how, in 1997, President Bill Clinton, Senate Majority Leader Trent Lott (R-Miss.) and House Speaker Newt Gingrich (R-Ga.) negotiated the first balanced-budget agreement in a generation, and how, in 2008, a bipartisan majority in a Democratic-controlled Congress gave President George W. Bush the unprecedented powers necessary to stem the financial crisis and prevent another Great Depression. And both Bush and his successor, President Barack Obama, had the courage to take highly unpopular actions to save our economy, resisting pressure from their base to put the national interest ahead of partisan politics.

Third, our leaders must be willing to make principled compromises. Finding the middle ground has never been easy, and nobody wants to lose a negotiation. But today, our leaders are equating compromise with moral failure, making it that much harder to begin a discussion, much less reach agreement.

Recognizing the importance of these principles in effective policymaking, in 2017 we formed the Aspen Economic Strategy Group, a group that is committed to evidence-based policymaking, civil discourse and exchanging policy ideas with those who hold different points of view.

Over the course of the past year, we collected policy ideas to address the barriers to broad-based economic opportunity and identified concrete proposals with bipartisan appeal. These proposals are being released Feb. 4 in the edited volume “Expanding Economic Opportunity for More Americans: Bipartisan Policies to Increase Work, Wages, and Skills” by the Aspen Institute.

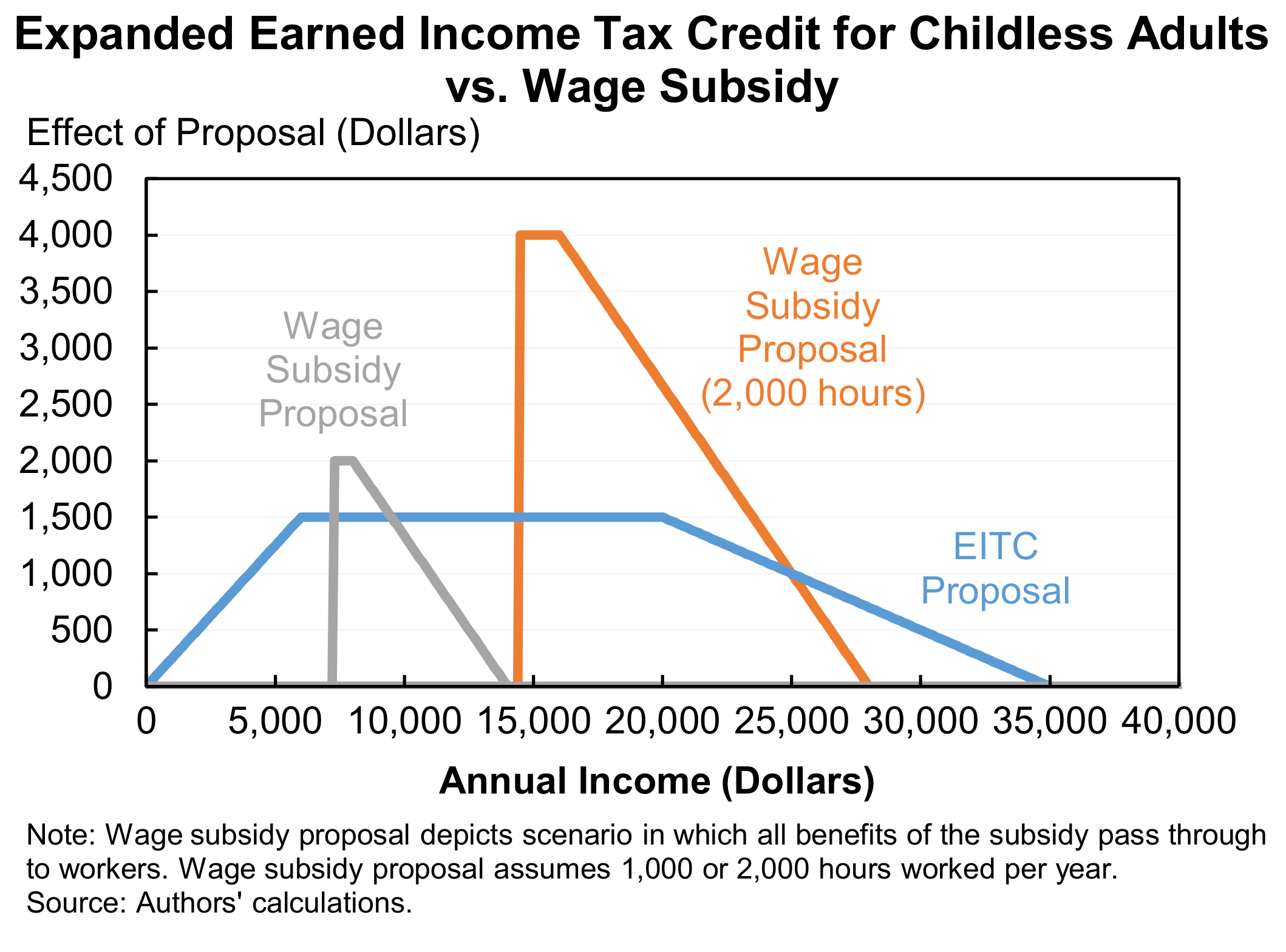

The policy ideas are based in evidence, not ideology, and are wide-ranging in scope, including massive federal investments in community colleges, dedicated strategies to promote the economic health of rural labor markets, sensible zoning reform to promote housing affordability and a payroll subsidy to offset the cost of minimum-wage increases on employers, among others.

We believe that practical ideas such as these provide a thoughtful starting place for policymakers and community leaders to work together to address our nation’s deep structural problems. But our leaders must first commit themselves to the principles of good governance that have sustained our democratic policymaking for generations. Doing so is as important to the health of our economy as it is to the strength of our democracy.

This article was originally published in the Washington Post.