For many high school seniors and their families, May 1st is “National College Decision Day,” when millions of students make a personal decision about their academic future. It is also a decision with financial implications that will shape much of their lives. While headlines often cite the ultra-competitive landscape for highly selective schools, recent years have brought about a drop in overall college enrollment. Some of this reflects pandemic-related disruptions to college plans. But recent survey data suggests that we might be seeing a more persistent turn away from college: more than half of Americans don’t even think college is worth the investment. This is very worrisome, as completing college is as important as ever to bolstering both individual economic security and America’s economic competitiveness.

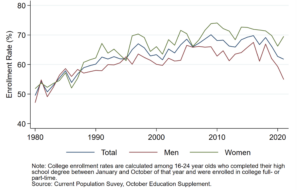

In April, a Wall Street Journal-NORC poll found that 56% of Americans think that a college degree is not worth the cost, the highest rate in the survey’s ten-year history. These attitudes are also reflected in the actions of our youngest generation, as fewer students opt to pursue a college degree. In February, the National College Clearinghouse reported the sixth straight year of declining enrollment in 2- or 4-year colleges. In 2021, there were 1.8 million fewer undergraduates enrolled in college than there were in 2017.

But the fact remains that overwhelmingly economic data show that a college degree confers meaningful economic advantages. Even in today’s tight labor market, college graduates find work much easier and tend to command significantly higher incomes. Today, the unemployment rate for those with a bachelor’s degree or greater is currently half that of those with a High School degree or GED.

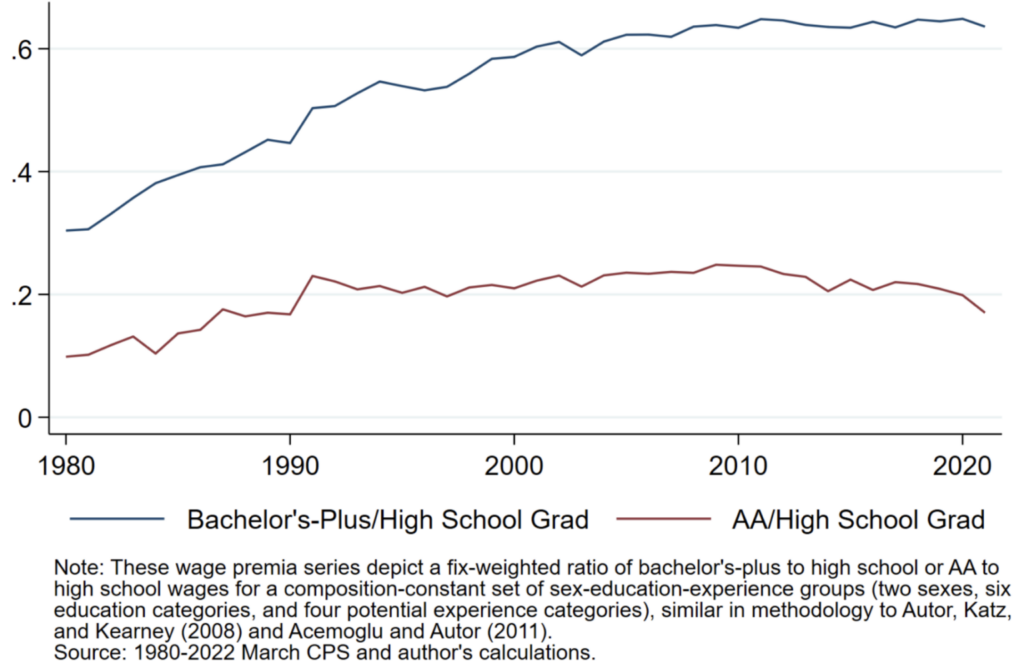

Estimates from the Aspen Economic Strategy Group find that the economic return to competing college remains at an all-time high. In 2021, Bachelor’s Degree holders earned 88% more per year on average than a worker with a high school degree, and Associate’s Degree holders earned 19% more. In dollar terms, the typical full-time full-year worker with a BA earned about $85,801 in 2021, compared to $53,854 for a worker with an AA and just $45,426 for those with a high school degree.

Indeed, the fastest growth in this so-called “college wage premium” was in the 1980s and 1990s, when technological advances like the personal computer and the internet caused a sharp increase in the demand for skilled workers that outpaced the supply of such workers that was available. If the recent past is a guide, the rapid advances we are experiencing today in automation and artificial intelligence will further increase the need for a highly skilled workforce. College remains the surest path for acquiring advanced skills.

It is understandable why many students and families suspect that college is no longer “worth it.” The inflation-adjusted “sticker price” of college tuition has been rising for years, and many students fear being burdened with loans after graduation. But more transparency and more accountability in the higher education sector—coupled with more informed choices by individuals—will increase confidence among prospective students that if they make smart decisions about where to go to school and what to study, a college degree is worth the investment of time and money.

College pricing is notoriously opaque, and students from low and middle-income families too often don’t realize that they would pay much less than that ever-increasing sticker price. In fact, the net price of a four-year college—which is what students pay after financial aid—has been falling since 2018 and is now lower than it was in 2006. The higher education sector must become more transparent about pricing so students are not deterred by sticker shock.

Furthermore, stories about people who paid too much for a degree that didn’t pay off are, regrettably, common. But recent research shows that on average, students who took on additional debt when federal loan limits were raised were more likely to finish their degree and went on to earn more later in life. In other words, the investment paid off. Of course, not all schools and not all degrees yield similar outcomes for comparable students, and colleges must become more accountable for student outcomes. Chronically poor performing schools should not receive federal dollars, and institutions should have stronger incentives to ensure students do not leave with crippling debt.

At the same time, students and parents can make use of resources available today to make wise choices. Tools like the College Scorecard enable would-be college-goers to readily compare results like graduation rates and after-college earnings across schools. By considering average outcomes of students who attended a particular school and earned a particular degree, prospective students can gain a reasonable picture of what their future holds down each potential path.

Just as high school seniors reach the end of one road and the start of another, today should also be an opportunity for higher education leaders and policy makers to commit to building on the strengths of our country’s higher education system, while making course corrections that will allow students to more readily make smart choices. Each student’s college choice is an investment in their future, and we must support and strengthen those investments, both for these students’ own economic futures and for our shared prosperity.

*This essay was originally published in TIME Magazine. You can read the complete article here.