This paper evaluates the current landscape of global trade and financial flows and proposes a set of reforms to support healthier forms of integration. Brad Setser finds that, despite the growing, bipartisan skepticism about the value of liberal trade, global economic integration remains surprisingly resilient. In fact, Setser argues, the immediate risk facing the global economy is more accurately described as unhealthy integration than fragmentation. Setser identifies two unhealthy forms of globalization that have proven to be resilient – those driven by corporate tax avoidance strategies and persistent trade and payment imbalances with China – and offers three policy reforms to address these risks.

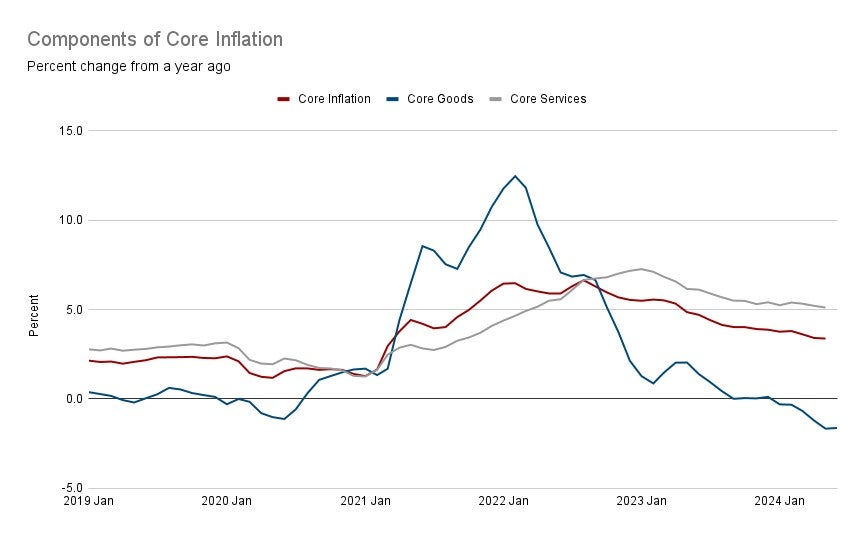

Tax avoidance tactics, such as the “Double Irish” strategy, have allowed major companies to route profits through offshore subsidiaries to minimize tax liabilities. The OECD’s 2015 base erosion and profit shifting (BEPS) reforms, aimed to curtail such practices by eliminating stateless income and zero-tax jurisdictions. The 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) subsequently further addressed the issue of international tax avoidance by reducing the corporate tax rate, ending deferral, and introducing two new special tax rates for Foreign-Derived Intangible Income (FDII) and Global Intangible Low-Tax Income (GILTI).

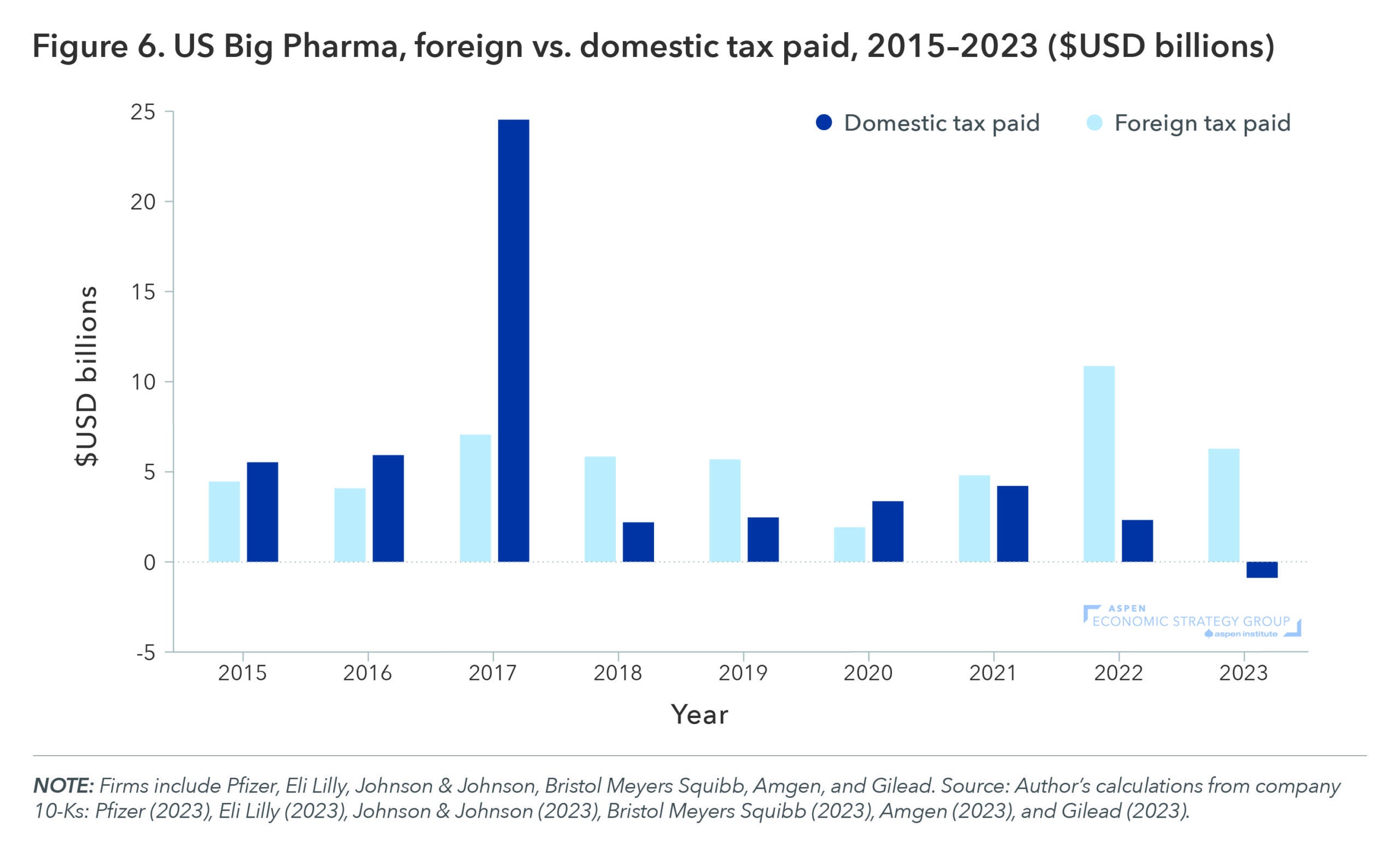

Despite these reforms, tax avoidance and offshoring are still considerable issues in the US tax system. The pharmaceutical industry serves as a prime example: US imports of pharmaceuticals have more than doubled since the TCJA, with imports primarily originating from tax havens such as Ireland, Singapore, and Switzerland. In 2023, seven of America’s largest pharmaceutical companies reported losing a combined $14 billion on their US operations while earning $60 billion abroad. The absence of reported profits in the US translates directly into a loss of federal tax revenues. Similar issues are present in other crucial sectors, leading to reduced domestic tax revenues and unhealthy global economic integration.

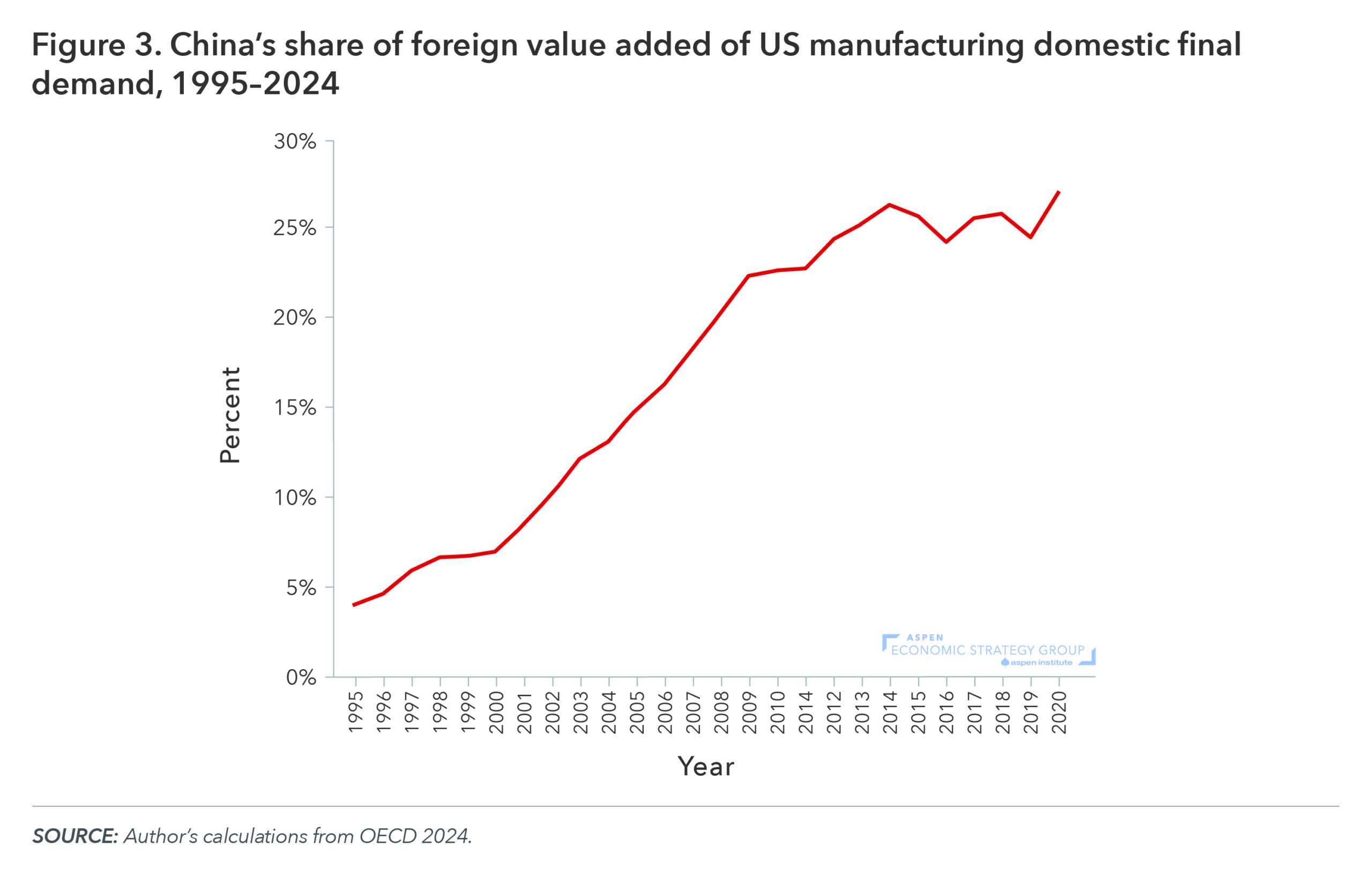

China’s domestic economic issues pose a further challenge to global economic integration. Recent data shows China’s economy is re-globalizing and exports have recently grown much faster than China’s own economy. However, this form of globalization is the result of high household savings rates and faltering domestic demand in China, which has led the country to rely again on exports to support its economic growth.

This export-led growth model is driven by extensive government support to favored sectors, mostly through the provision of cheap equity and cheap debt financing. Furthermore, the high level of savings creates internal imbalances in the United States, the eurozone, and in China, fueling bubbles and bad debts. The Chinese property sector has long absorbed the excess savings, but property construction is expected to normalize, creating greater pressure on exports to drive growth in China.

Setser offers three concrete steps which would start to define a path toward a healthier form of globalization.

1. Reform the US corporate tax code. Limiting offshoring, increasing the GILTI rate from 10.5 percent to 15 percent, limiting US firm’s ability to deduct R&D expenses of intellectual property in offshore subsidiaries, and making the sale of a firm’s intellectual property from one international subsidiary to another a taxable event would reduce profit shifting while raising US tax revenue.

2. Create subsidy sharing agreements among allies in key sectors. In industries such as electric vehicles and steel, subsidies sharing agreements and increased policy coordination between the US and EU would expand the market size for American and European firms and lower costs.

3. Address China’s internal imbalances. US policymakers and international institutions such as the IMF should pressure China to change its export-led growth model and address its internal economic imbalances.

Suggested Citation: Setser, Brad. 2024. “The Surprising Resilience of Globalization: An Examination of Claims of Economic Fragmentation” In Strengthening America’s Economic Dynamism, edited by Melissa S. Kearney and Luke Pardue. Washington, DC: Aspen Institute. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13973914.