Archives: Publications

These are AIESG Publications

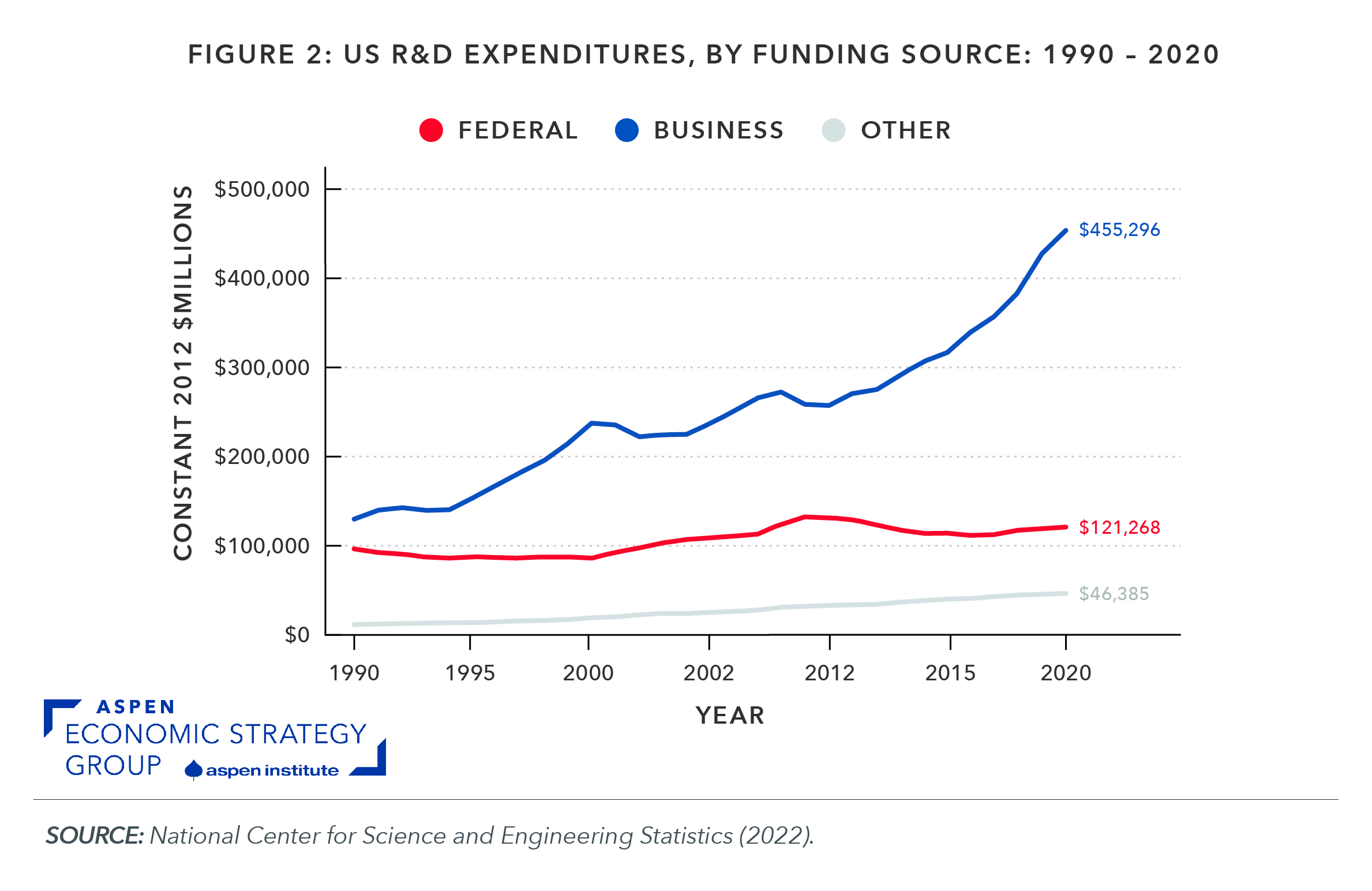

Figure 1A: Gross expenditures on R&D (GERD) and R&D intensity: 2019 or most recent data year, top 17 countries

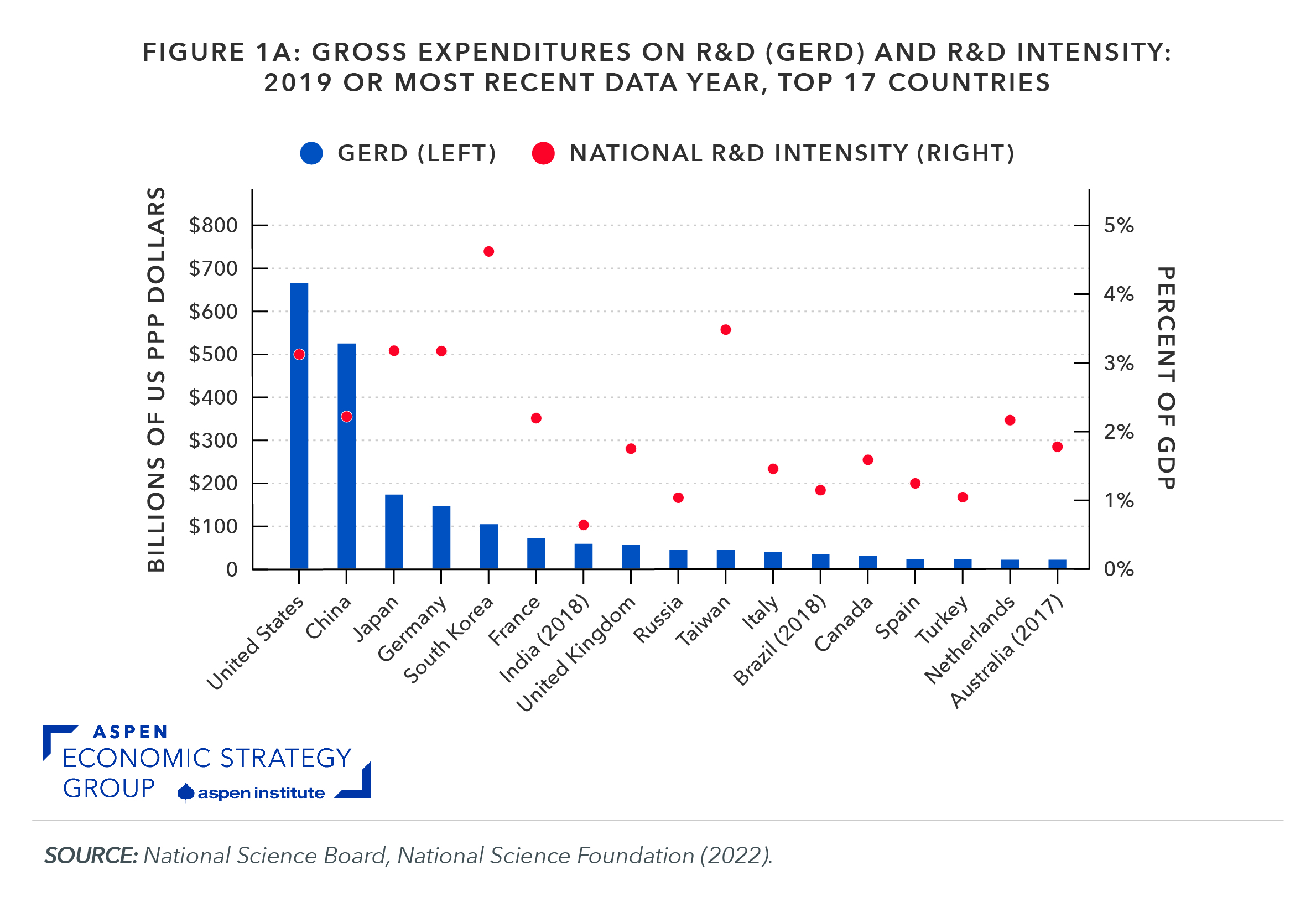

Figure 1B: Gross domestic expenditures on R&D, by selected country: 1990-2019

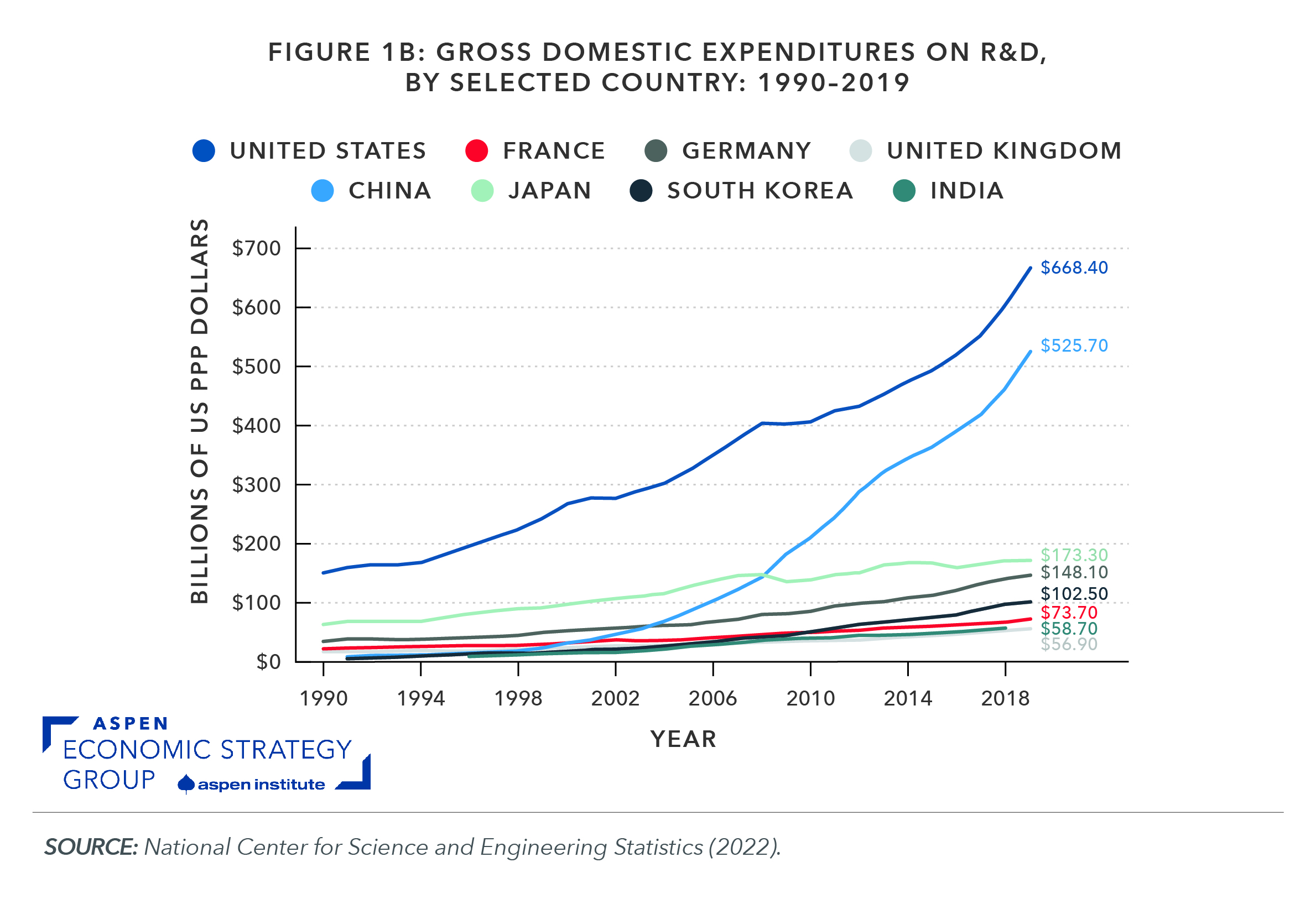

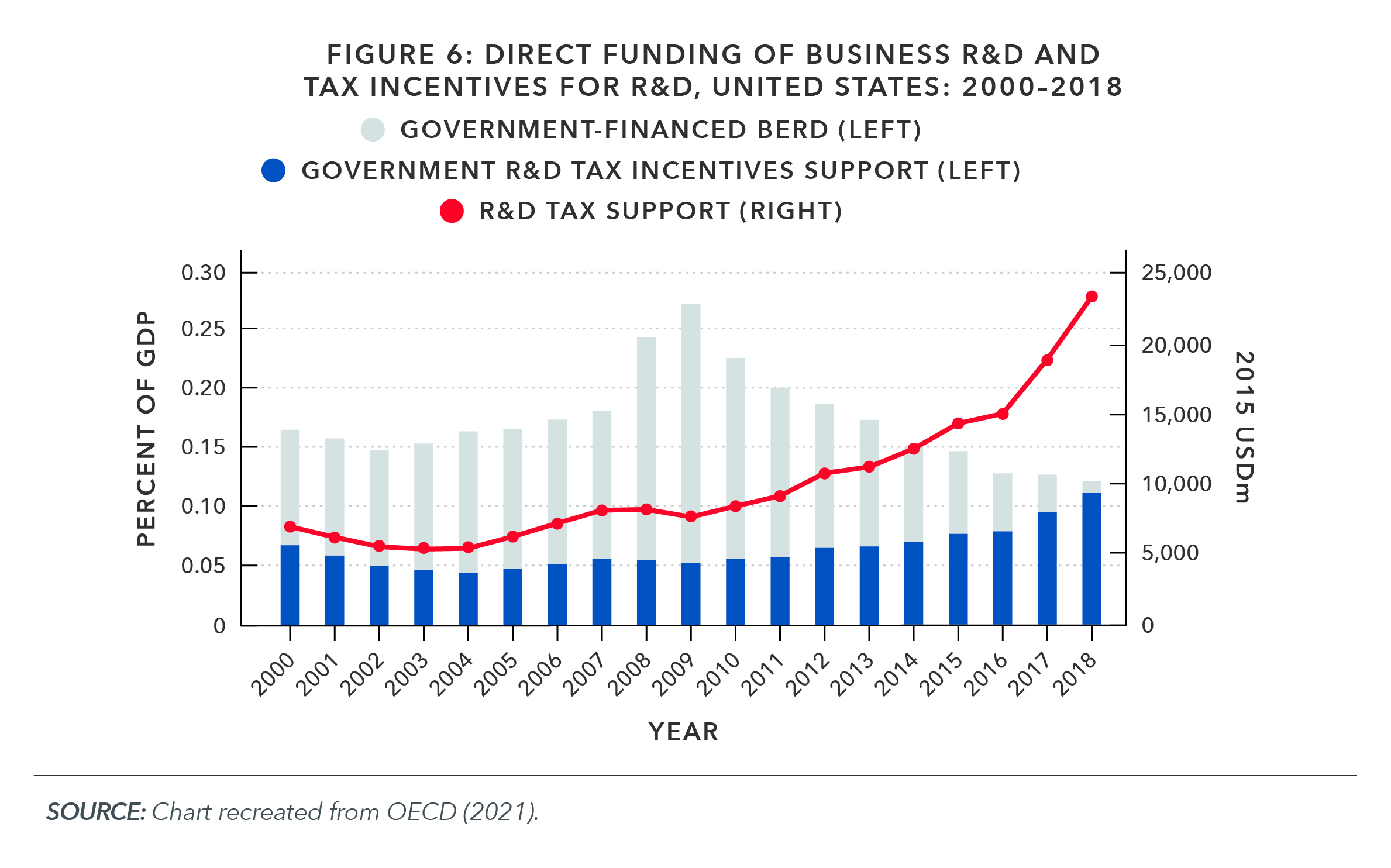

Figure 6: Direct funding of business R&D and Tax Incentives for R&D, United States: 2000-2018

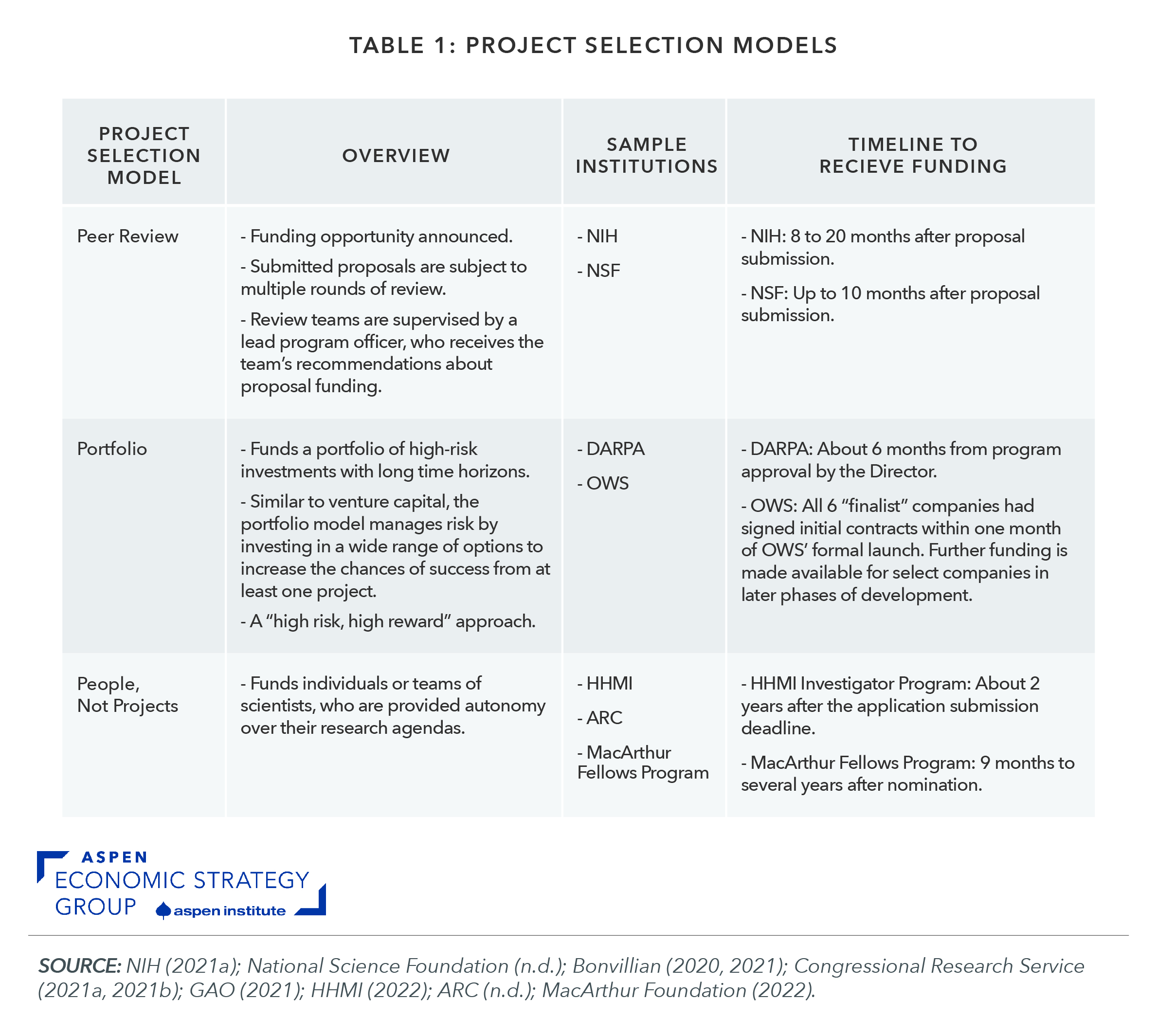

Table 1: PROJECT SELECTION MODELS

IN BRIEF: The Wide Class Divide in Family Structure

BRIEFLY:

Children in the US are far less likely to be raised in two-parent families today than they were in prior decades, a shift Aspen Economic Strategy Group (AESG) director Melissa Kearney explores in her new book, The Two-Parent Privilege.

US children are now more likely than those in any other country to live in a one-parent home. This trend has been driven by a reduction in marriage among US adults, including parents. From 1980 to 2019, there was a dramatic decline in the share of children living with married parents—the share fell from 77 percent to 63 percent. The largest declines were among children of mothers without a college degree, leading to what Kearney refers to as a “college gap” in children’s household structures. This trend both reflects and exacerbates a wide class divide in economic circumstances and security: without the resources and support of a two-parent family, children are less likely to graduate high school, get a college degree, or have high earnings in adulthood. Consequently, the class gap in family structure heightens economic inequality and perpetuates it across generations.

WHAT TO KNOW:

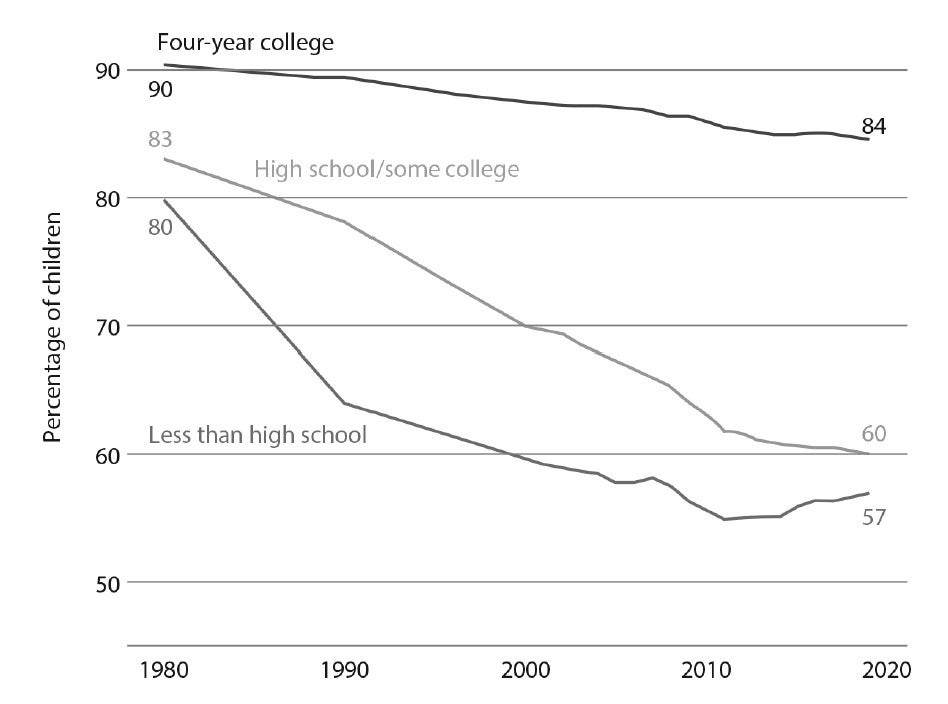

- Far fewer children are raised in two-parent households today, and that decline has occurred mostly outside the college-educated class. From 1980 to 2019, the share of children living with married parents fell from 77 percent to 63 percent. Importantly, this trend was not driven by high-income mothers raising children alone: the share of children living with married parents fell only 6 percentage points among those whose mother had a four-year college degree, from 90 percent to 84 percent. In contrast, among children whose mothers had only a high school degree or some college, the share fell from 83 percent to 60 percent and from 80 percent to 57 percent among children whose mother had less than a high school degree.

Figure 1: Percentage of children living with married parents, by maternal education level

Source: The Two-Parent Privilege (author’s calculations using 1980 and 1990 US decennial census and 2000 2019 US census American Community Survey, with observations weighted using child’s survey weight)

- The socioeconomic class gap in family structure contributes to widening inequality and reduced social mobility in the US. Families are a source of both financial and nonfinancial resources that benefit children. Parents provide not only love and strong connections but time and money as well. When two parents are present in a household, they tend to have more income, more time, and more energy to devote to a child’s development. Crucially, the class divide in two-parent households is partly driven by inequality of economic opportunities, but it also widens class gaps. Parents with less education have less economic security, and they are less likely to be married and raise their children together. Their children grow up with fewer resources and opportunities: low-income families spend about half as much on child education and enrichment activities as do those in the middle of the income distribution ($1,421 per child in 2007 versus $750 for low-income parents). Further, children of unmarried parents spend 7.6 fewer hours per week with their children. These kids, in turn, are more likely to get in trouble in school, to be involved in crimes as adolescents, to have lower incomes as adults, and to have children out of marriage—starting the cycle all over again.

- Young boys are particularly responsive to parental input and to the presence of fathers or father figures. Raising a family alone often means having fewer financial resources and less time and emotional bandwidth to offer one’s children. Research by the economists Marianne Bertrand and Jessica Pan found that boys are more sensitive than girls to these differences in resources, contributing to the relatively worse outcomes of boys as compared to girls. For instance, the elevated rate at which boys get in trouble at school is even higher among boys from single-mother households. Other research has found that beyond the beneficial presence of fathers in one own’s household, boys—Black boys in particular—benefit from having more fathers in the neighborhood. Research from Harvard University’s Opportunity Insights team found that the presence of Black fathers in a neighborhood is one of the strongest predictors of whether Black boys will move up the income distribution later in life.

- This rise in children living in single-parent households is not driven by divorce and comes despite a decline in births among young women. Today, a smaller share of unmarried mothers has been divorced and a greater share has never been married than in previous decades. In 2019, 52 percent of unpartnered mothers (meaning mothers living in a household without either a spouse or an unmarried partner) had never been married, as compared to 22 percent in 1980. Further, as Kearney and Phil Levine report in their 2022 AESG policy chapter, birth rates in America have fallen among women under 30 years old, with especially steep declines among teenagers. In sum, the rise in single-mother households reflects a rise in nonmarital births, not an increase of births to teen or young women—and it is not a function of rising divorce.

- These trends reflect, in part, reduced economic opportunities among non-college-educated men and changing social norms around marriage and childbearing. Marriage is both a source of companionship and an economic partnership. As men without a college degree have lost ground economically (both in absolute terms and relative to women) their marriage rates have fallen. From 1980 to 2020, among men without a four-year college degree, employment rates fell, and median inflation-adjusted earnings hardly changed. Among working men ages 30 to 50, in both 1980 and 2020, median earnings were just below $49,000 for those with just a high school degree and just below $35,000 for those with less than a high school degree. Over the same time frame, marriage rates among these two groups of men fell sharply, from nearly 80 percent to less than 55 percent. This trend stands in contrast to the situation among college-educated men, whose earnings over this time soared and whose marriage rates fell much less, from about 80 percent to 70 percent. Indeed, the decline in domestic manufacturing jobs in the US has been associated with reduced economic opportunity for men without a college degree—and economists have found that reduction caused a decline in marriage rates and a rise in the share of children living in single-mother homes.

- As relaxed norms around nonmarital childbearing have emerged, it is not clear that reversing this economic decline is a silver bullet to turning marriage rates around. In a 2018 study, Kearney and Riley Wilson found that areas where men without a college degree experienced increased economic opportunity (from local fracking booms) saw a rise in births—but this rise was in equal proportion among married and unmarried parents, and it brought no associated rise in marriage rates. Their study contrasts this family-formation response with the response to a similar economic shock in the 1970s and 1980s. Local coal booms at that time led to an increase in male earnings in coal-producing communities; they led, too, to an associated increase in marriage and in births to married couples, as well as to a decrease in the share of nonmarital births. This research suggests an important interaction between economic shocks and prevailing social norms; the high share of children being born and raised outside marriage today likely reflects both economic and social conditions.

- To address this trend, Kearney concludes that the US needs a dedicated effort to strengthen families, especially among groups for whom one-parent homes have become commonplace. The evidence marshalled in Kearney’s book suggests that both the evolution of social norms away from marriage and two-parent families and the economic struggles of non-college-educated men have contributed to the rise in the share of children living with only one parent (typically their mother) and to a wide class gap in family structure. She concludes that addressing the resulting challenge will require improving the economic opportunities of non-college-educated men, which will make marriage a more attractive option, as well as promoting a norm of two-parent homes for children. She also suggests that US policies and programs should promote strong and healthy family units in cases where parents cannot, should not, or do not want to be married, and they should continue to promote and scale evidence-based programs that help children from under-resourced, often single-parent, homes.

THE BOTTOM LINE:

Family structure is often avoided as a topic of policy conversations, as it is a personal and sensitive topic, and less obviously responsive to policy intervention than other issues related to inequality and social mobility, like educational attainment or wages. But as both symptoms and causes of economic challenges in the United States—including widening income inequality and reduced economic mobility—the high share of US children being raised in a one-parent home and the wide class gap in family structure cannot be ignored. Kearney argues in her new book that strengthening families must be a US policy priority: doing so will be key to achieving our nation’s aim to advance child well-being, break intergenerational cycles of economic disadvantage, and promote equal opportunity and social mobility.

Press Release: Why Drug Pricing Is Complicated

Aspen Economic Strategy Group releases new paper by Kellogg’s Craig Garthwaite and Amanda Starc

WASHINGTON, DC | WEDNESDAY, AUGUST 30, 2023 — The Aspen Economic Strategy Group (AESG) today released a new paper, “Why Drug Pricing is Complicated,” by Craig Garthwaite and Amanda Starc of Northwestern’s Kellogg School of Management. The paper details the complicated drug pricing structure in the United States and offers possible policy solutions. Yesterday, the Biden Administration announced 10 drugs that will be subjected to price negotiations with Medicare.

“The blunt and somewhat clumsy approach of the Inflation Reduction Act and many other proposed policies toward drug pricing primarily reflects society’s frustration over high pharmaceutical prices,” stated Garthwaite and Starc in the paper. “But making a better system means finding the right balance between affordable access to products today and access to innovative new drugs in the future.”

The paper states that high prices are a deliberate feature of the complex system by which new products are brought from the scientific bench to the patient’s bedside. Garthwaite and Starc say the goal as a society should not be focused simply on lowering prices but instead on increasing value.

On the role of Medicare: While the US health care system is often described as a free market system dominated by private firms, in reality government payers of various types are a meaningful part of the payment system for pharmaceuticals. As of 2017, the largest single payer is private health insurance, which accounts for 42 percent of all spending, while Medicare accounts for 30 percent and Medicaid another 10 percent. Given their massive scale, the statutory payment rules implemented by these government payers can have wide-ranging implications.

On large-molecule drugs driving rising drug prices: Spending is driven by specialty drugs and branded drugs. From 2011 to 2021, specialty medications grew from 28 to 55 percent of overall drug spending (IQVIA 2022). This growth was driven by increased spending for autoimmune (459 percent) and oncology (326 percent) products. A recent analysis of sales data shows that only 20 percent of prescriptions are for branded drugs, yet, over 80 percent of drug spending is on branded drugs, because they are meaningfully more expensive than their generic counterparts.

Retail consolidation also affects prices: Patients purchase prescription drugs from a pharmacy, either in a physical location or by mail. Over time, this market has become increasingly concentrated. In 2022, the five largest pharmacies were CVS Health (both mail order and retail), Walgreens Boots Alliance, Cigna (mail order), UnitedHealth Group (OptumRx mail order), and Walmart Stores. Together these five account for 64 percent of all retail sales (Fein 2023b). Larger pharmacies may have more leverage in negotiations with both wholesalers and buyers. This leverage could allow them to earn more margin on the spread between the acquisition price and the sales price of the drugs. It also allows them to demand greater dispensing fees for medications—fees that can represent the majority of the pharmacy profits from branded expensive drugs. Left behind in this pattern of consolidation are the remaining independent pharmacies that have little market power and therefore have experienced consistent decreases in reimbursements for their services.

On collusion in the market for generic drugs: Alleged anticompetitive behavior has also led to skyrocketing prices. For example, an active collusive ring of generic manufacturers led to price hikes for over one hundred drugs. The scheme generated $12 billion of additional profit for drugmakers (Cuddy 2020). Firms like Mark Cuban’s CostPlus drugs are attempting to deal with collusion in the market for generics. The FDA should continue to evaluate the approval process to look for additional efficiencies that would decrease entry costs.

On the role of pharmacy benefit managers and rebates: An area of rare bipartisan consensus is that PBMs are exploiting their position as middlemen to siphon money from both patients and pharmaceutical firms. PBMs manage the pharmaceutical benefit of a consumer’s insurance plan and negotiate rebates with drug wholesalers in exchange for allowing consumers access to that drug. Frustrated by rising drug prices, people are looking for a scapegoat, and a system of shrouded prices set by large firms makes a convenient target. However, it would be unwise to limit the ability of PBMs to negotiate large discounts. Instead, we should move to a system where all payments between manufacturers and PBMs flow first to payers before being split with PBMs.

The IRA also includes changes beyond price negotiations meant to control drug price spending: The IRA changes the cost structure of prescription insurance coverage (Part D) to remove any enrollee responsibility for spending once they reach $7,400 in out of pocket expenses. In addition, the government share of spending in this period was reduced to 20 percent, while Part D plans are now responsible for 60 percent. There are a number of drugs that would automatically put patients at this limit each year simply as a result of their chronic – and known – condition.

The paper concludes by offering possible solutions to address high cost of prescription drugs in the US market without threatening US innovation in drug development. In addition to the proposals outlined above, possible solutions include ending rebates that middlemen negotiate with drug manufacturers and making the price negotiation system more transparent; creating upper limits on the amount of cost sharing that can be charged to consumers; providing copayment assistance in the commercial market; and encouraging more competition among pharmacies.

Click here to read the full paper.

To speak with authors, contact Sean Scanlon at sean@econstrategygroup.org or 847-644-9882.

IN BRIEF: Cutting the Safety Net Is Not an Effective Way to Reduce Government Spending

BRIEFLY…

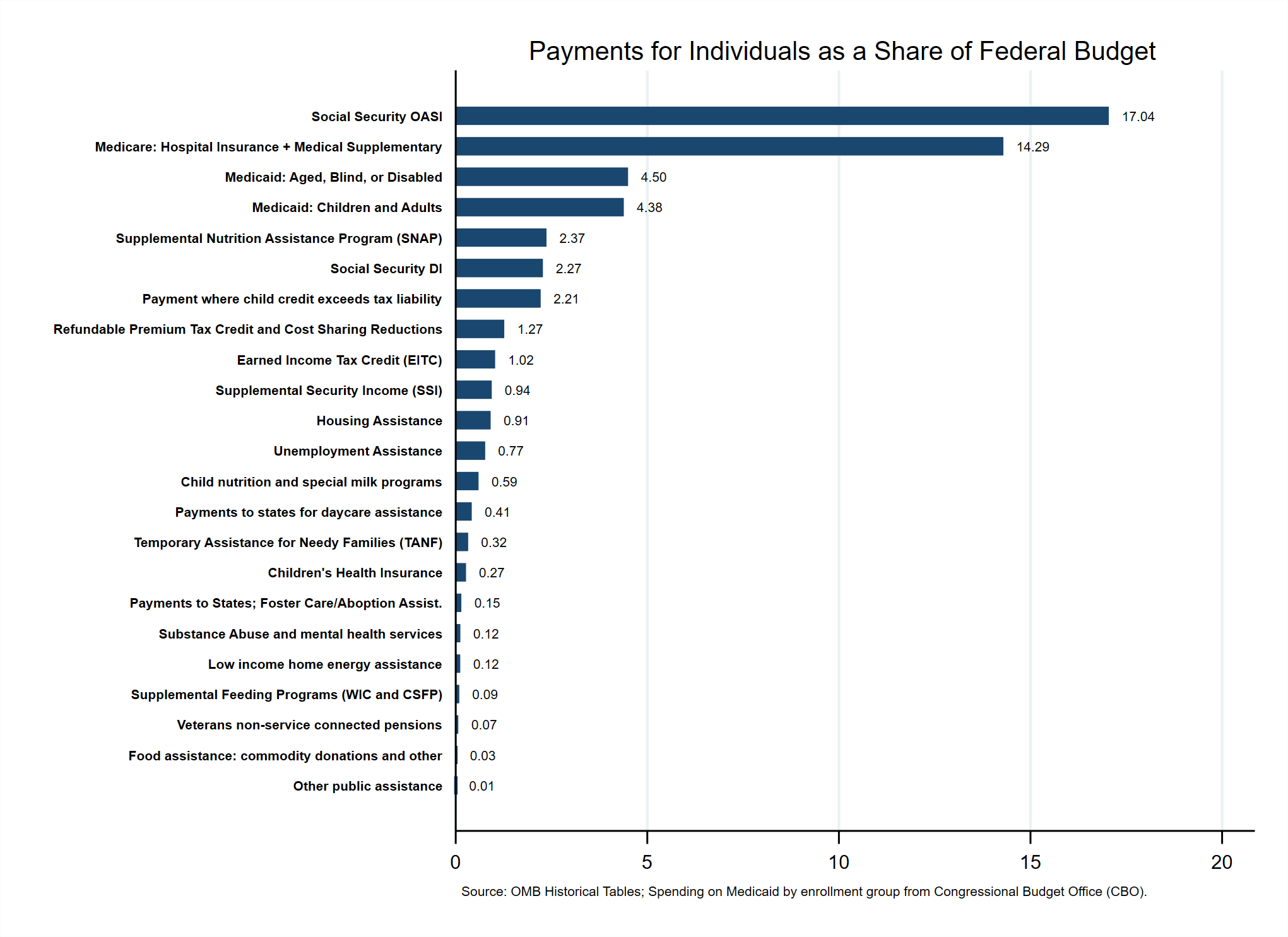

High-stakes negotiations over the debt limit center on ways to bring government spending more in line with government revenues. The political contours of the debate have excluded cuts to Social Security and Medicare from consideration, as well as the possibility of raising taxes. With these options off the table, much of what is left to consider for budget cuts is a series of programs that provide services and supports to low-income individuals and families. Some congressional policy makers are suggesting that federal spending cuts should come from tightened eligibility and reduced spending on programs whose primary function is to provide health insurance, food purchasing support, and conditional cash assistance to low-income individuals and families with children. Among the three programs at the center of the discussion — the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), and Medicaid – spending on SNAP and TANF amounts to less than 3% of total federal outlays in 2022 and Medicaid spending on children and adults (as opposed to the aged, blind, or disabled) amounts to less than 5% of the $6.2 trillion in 2022 federal government outlays. Since all three programs have been documented to provide large public benefits to vulnerable populations of Americans, cutting them is neither an effective way to rein in the spending that is driving up US debt, nor is it in the nation’s long-term interests.

WHAT TO KNOW

- The federal government’s two main cash or near-cash assistance programs that provide support to non-elderly, able-bodied low-income individuals and families with children made up a combined 2.7% of federal outlays in 2022 (see chart). The largest of these, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, formerly known as Food Stamps) provides low-income families and individuals with funds to purchase food. In 2022, the federal government spent $149 billion on SNAP across an average of 41 million individuals each month. The Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program is much smaller and provides time-limited cash assistance to adults with child dependents. Federal TANF spending totaled $20 billion in 2022, reaching an average of 1.9 million beneficiaries each month. TANF is administered as a grant to states, and in FY21 only 22.6% of all TANF spending was paid out in terms of cash benefits, with the remainder spent on services.

- In addition to the fact that they make up a relatively small share of Federal spending, budget savings from restricted eligibility coming from enhanced work requirements for these programs are likely to be even smaller. The programs already include some degree of work requirements and time limits. Since the creation of the program in 1996, TANF cash assistance has been tied to work requirements. The SNAP program offers limited assistance to able-bodied adults without child dependents, thereby effectively imposing work requirements for sustained assistance. Specifically, able-bodied adults without dependents are only eligible for benefits for 3 months in any 26-month period, unless they fulfill certain work requirements.

- Medicaid spending on children and adults (as opposed to the aged, blind, or disabled) amounts to 4.4% of the $6.2 trillion in 2022 federal government outlays. Medicaid provides public health insurance to adults and children whose family income falls below specified income thresholds, as well as to adults with qualifying disabilities and those in long-term care facilities. The program had total outlays of $592 billion in 2022, comprising 9.4% all federal outlays that year. However, payments for children and non-disabled adults accounted for just under half of (46%) of Medicaid spending that year, or a total of 4.4% of all federal outlays. On average in each month of 2022, 37 million children, 39 million non-elderly adults, and 17 million disabled or elderly individuals received Medicaid benefits. On a spending per-enrollee basis, children made up an even lower share of costs: outlays on children averaged $1,720 per child in 2022, compared to $14,520 for each elderly Medicaid enrollee. Tightening eligibility requirements (through work requirements or otherwise) on nonelderly and nondisabled adults – or specifically on parents and children — would yield only limited cost savings.

- Funding cuts that reduce spending on children’s health insurance and nutrition come at a social cost. More than 10 million U.S. children — 14.4 percent — lived in poverty in 2019, according to government statistics. Income assistance programs like SNAP and TANF, as well as access to health insurance through Medicaid, are a crucial source of resources for this large share of children improving their current conditions while also bringing future returns. Evidence from academic research shows that Medicaid spending on children improves their long-term health and economic outcomes, ultimately saving the government money. In other words, this spending constitutes an investment in our nation’s youth and future workforce. Similarly, research has documented that access to SNAP benefits for low-income children leads to long-term improvements in health and economic self-sufficiency, and is a cost-effective investment in young children.

- The share of government spending on children stands in contrast with the share of resources devoted to older age Americans. Social Security and Medicare, which provide cash benefits and health insurance to the elderly, comprise a large share of federal government spending. Combined, the Social Security Old Age & Survivors Insurance and Medicare programs comprised 31.3% of federal outlays in 2022, providing benefits to 57 million and 65 million recipients, respectively. Spending on these programs is expected to rise further as a larger share of the country’s population enters retirement age. Absent significant reforms or benefit cuts, these two programs are projected to reach a combined 39.3% of outlays by 2028. On the other hand, the share of federal outlays for individuals excluding Social Security and Medicare is estimated to fall by more than half to 16.5% of all spending by 2028. If policymakers intend to address the budget deficit by reining in spending on individuals, these two programs are the place where there is the potential for meaningful reductions in budget outlays, and they could pursue spending cuts on these programs that maintain the distributional goals of progressivity and have negligible effects on human capital development and economic growth.

- Relatively modest increases in spending on children’s benefits, when compared to the level of spending on older Americans, have been shown to have a powerful effect on reducing child poverty. Spending on children increased temporarily in 2020 and 2021, through expanded SNAP benefits and an enhanced, fully refundable Child Tax Credit (CTC). Spending on SNAP increased modestly from 2.1% of outlays in 2015 to 2.4% in 2022, and the CTC increased from 0.56% of outlays in 2015 to 2.21% in 2022. This spending proved powerful in reducing material hardship among children, with measures of child poverty falling by 50% in 2021. The enhanced CTC itself is estimated to have cut food insufficiency by 25%. Both measures have since expired, however, and federal spending is set to return to shares seen before the pandemic.

THE BOTTOM LINE

The looming issue of the US federal government debt ceiling has focused attention on government spending and the need to bring outlays more in line with revenue. Reining in government deficit spending is ultimately in the nation’s long-term economic interest. However, how the federal government proceeds with spending cuts matters greatly for both the path of government spending and the growth and distributional consequences. Though federal outlays in the form of spending on individuals are concentrated largely on the elderly population through Social Security and Medicare, it is spending on children that yields large social returns in terms of improved health, human capital, economic self-sufficiency, and earnings. Rather than one-time expenditures, these programs are better viewed as initial investments in a healthier, better-skilled future generation. Cutting spending on those programs will have only a small budgetary impact, but potentially large negative long-term effects.

Editor’s Note: The analysis in this memo was jointly produced with EconoFact.

IN BRIEF: The Who, What, and Why of Declining College Enrollment, 2019-2021

BRIEFLY…

College enrollment in the US declined among recent high school graduates in the past couple of years, even as the economic returns to a college degree remain substantial – see this previous IN BREIF. In this post, we show that this drop in college enrollment was concentrated among men, and it was not limited to any particular race or ethnic group of men. Furthermore, labor force participation rates for young men remain depressed. As pandemic-related disruptions abate, it is important to help the young adults whose college plans and entry into the workforce were disrupted to get back on track. It is equally important to ensure that new high school graduates experience higher rates of college enrollment and transitions to the workforce.

WHAT TO KNOW

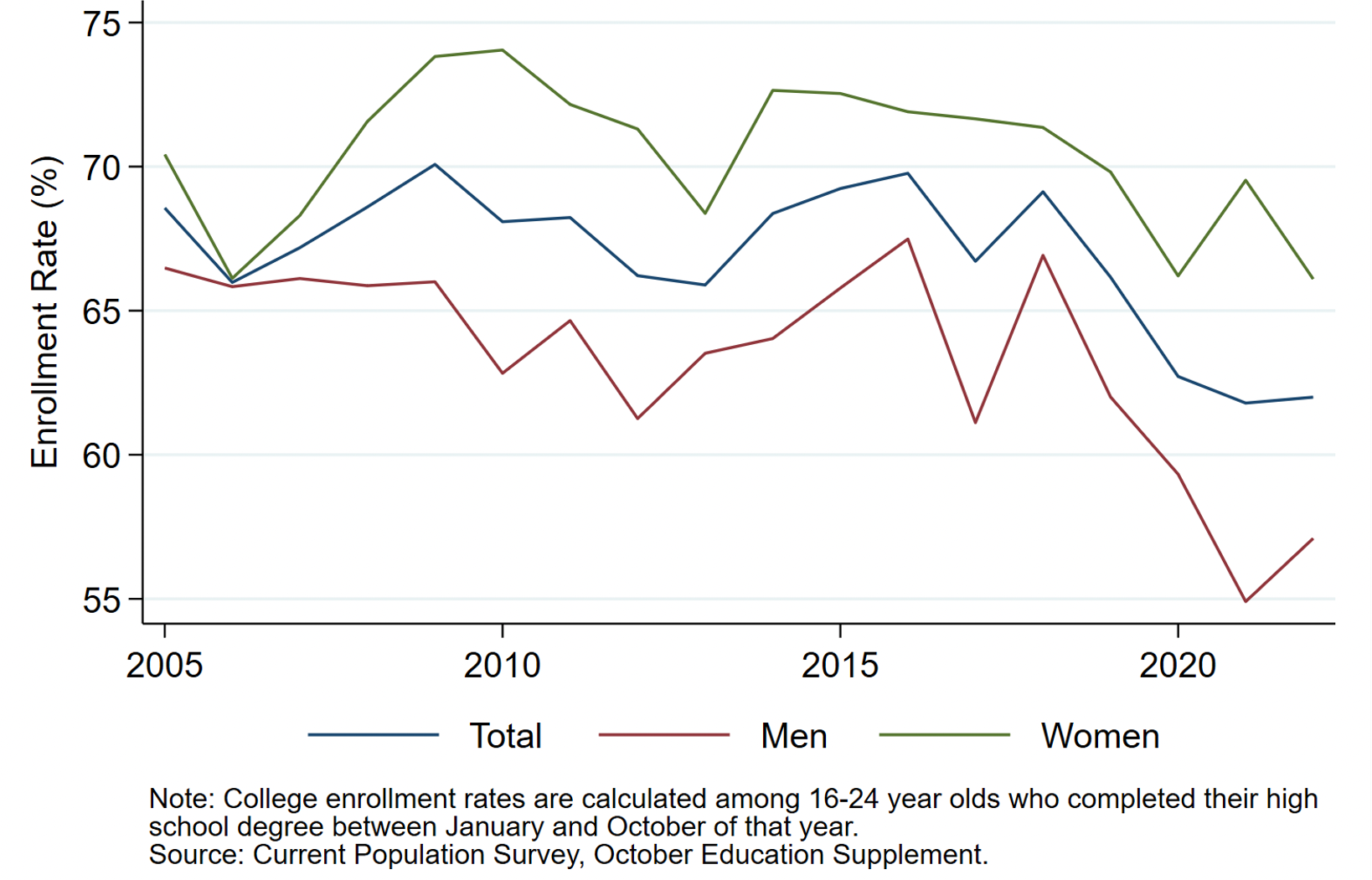

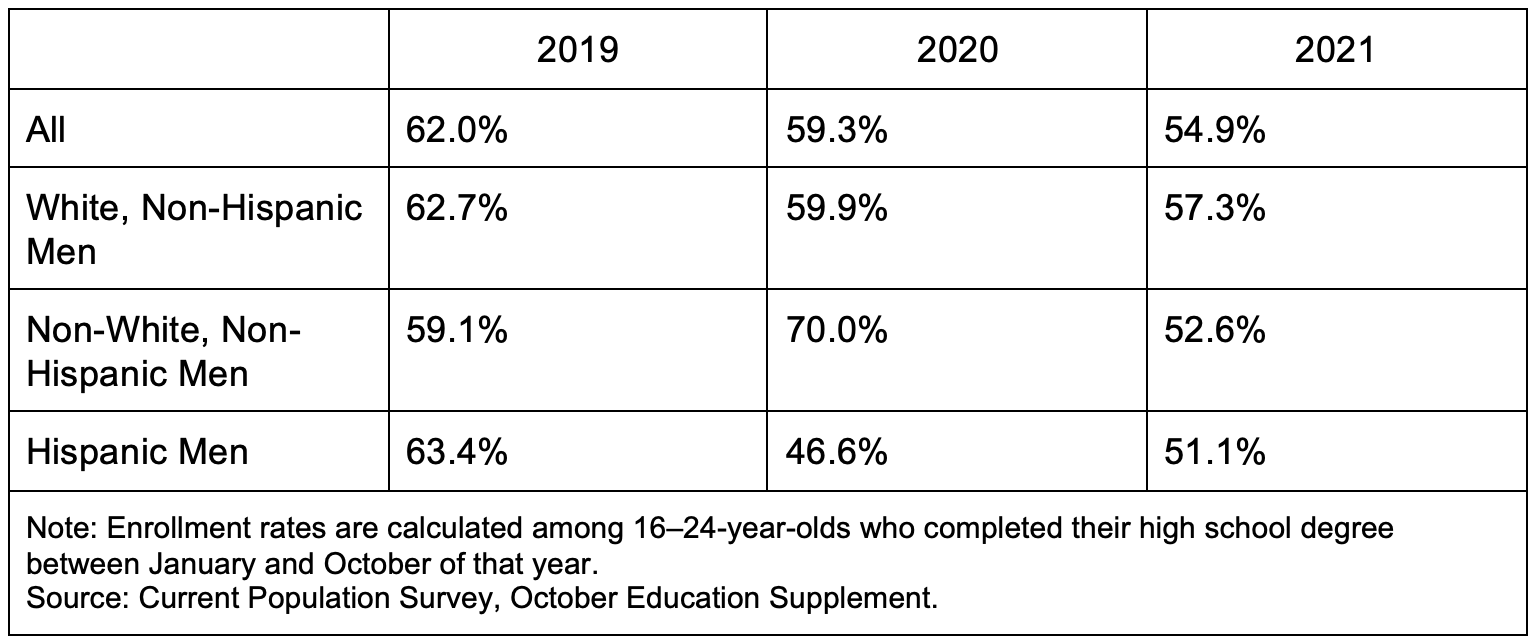

- Men have driven the recent decline in college enrollment out of high school. Among all recent high school graduates, college enrollment rates fell from 66.2% in 2019 to 61.8% in 2021. For men, just 54.9% of high school graduates enrolled in college in 2021, down from 62.0% in 2019. Among women, rates of enrollment remained more stable over this time period, falling slightly from 69.8% to 69.5%. Top-line data just released for 2022 indicate that the declines might be tapering off; overall enrollment is holding steady at 62.0% and men’s college enrollment rate was at57.1% in 2022, which is higher than in 2021, but still below pre-pandemic levels.

Figure 1. College Enrollment Rates of New High School Graduates

- The pandemic-era decline in college enrollment out of high school occurred across men of most major race and ethnic groups. Among White, Non-Hispanic men, enrollment rates fell from 62.7% to 55.3%; the enrollment rate among Non-White, Non-Hispanic men dropped from 59.1% to 52.6%. Hispanic men experienced the largest drop between 2019 and 2021 – from 63.4% to 51.1%.

Table 1. “Immediate” College Enrollment Rates of Recent High School Grads, Men

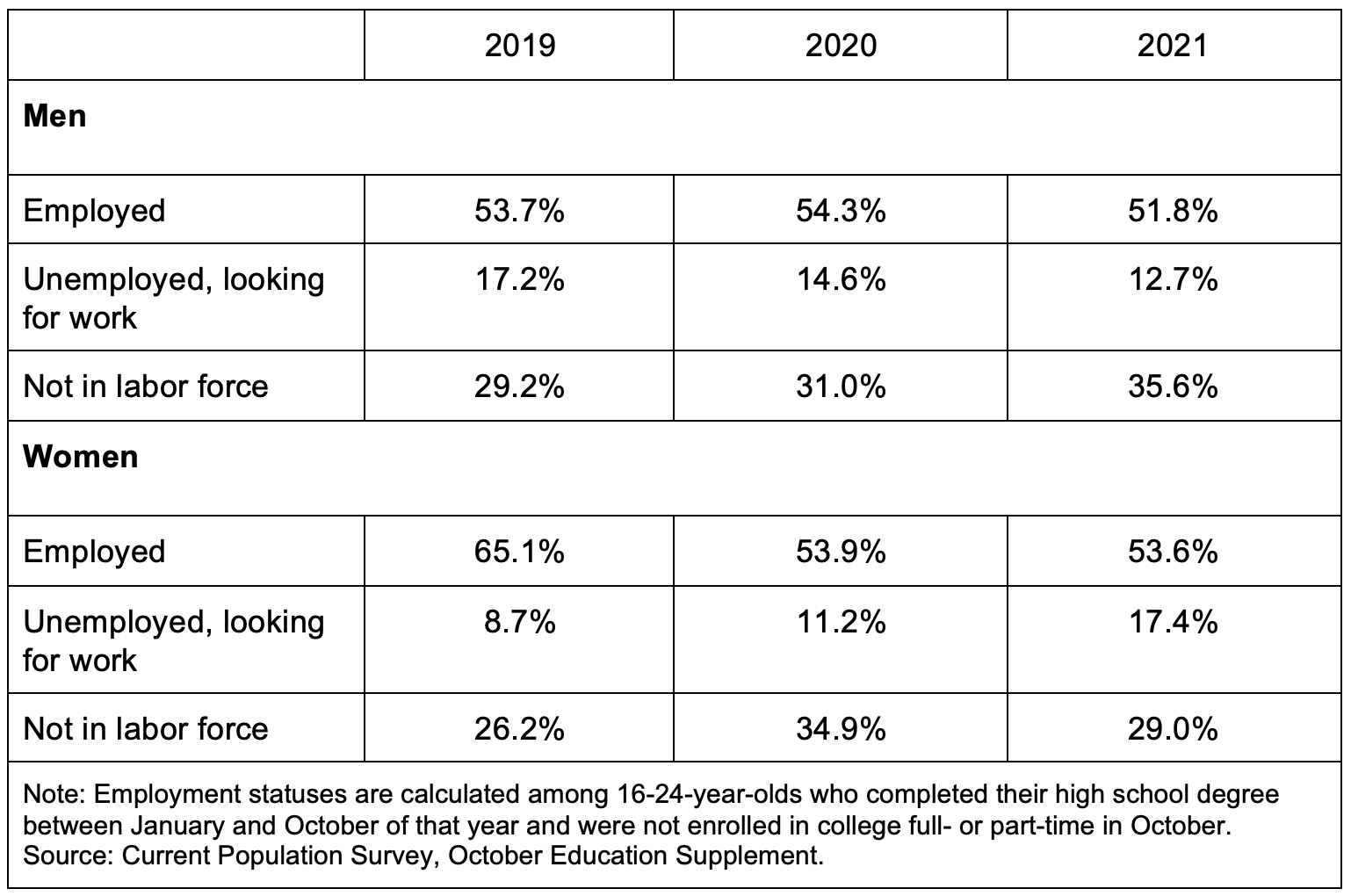

- These men and women graduating but not enrolling in college are less likely to be in the labor force than those in previous years who graduated but did not enroll in college. Despite anecdotal evidence that high schoolers are foregoing college to take advantage of the tight labor market, On the other hand now, the rate of male graduates who are neither in college nor in the labor force rose 6 percentage points and the share of women not in college and not in labor force rose 3 percentage points.

Table 2. Labor Force Status of Recent High School Graduates Not Enrolled in College

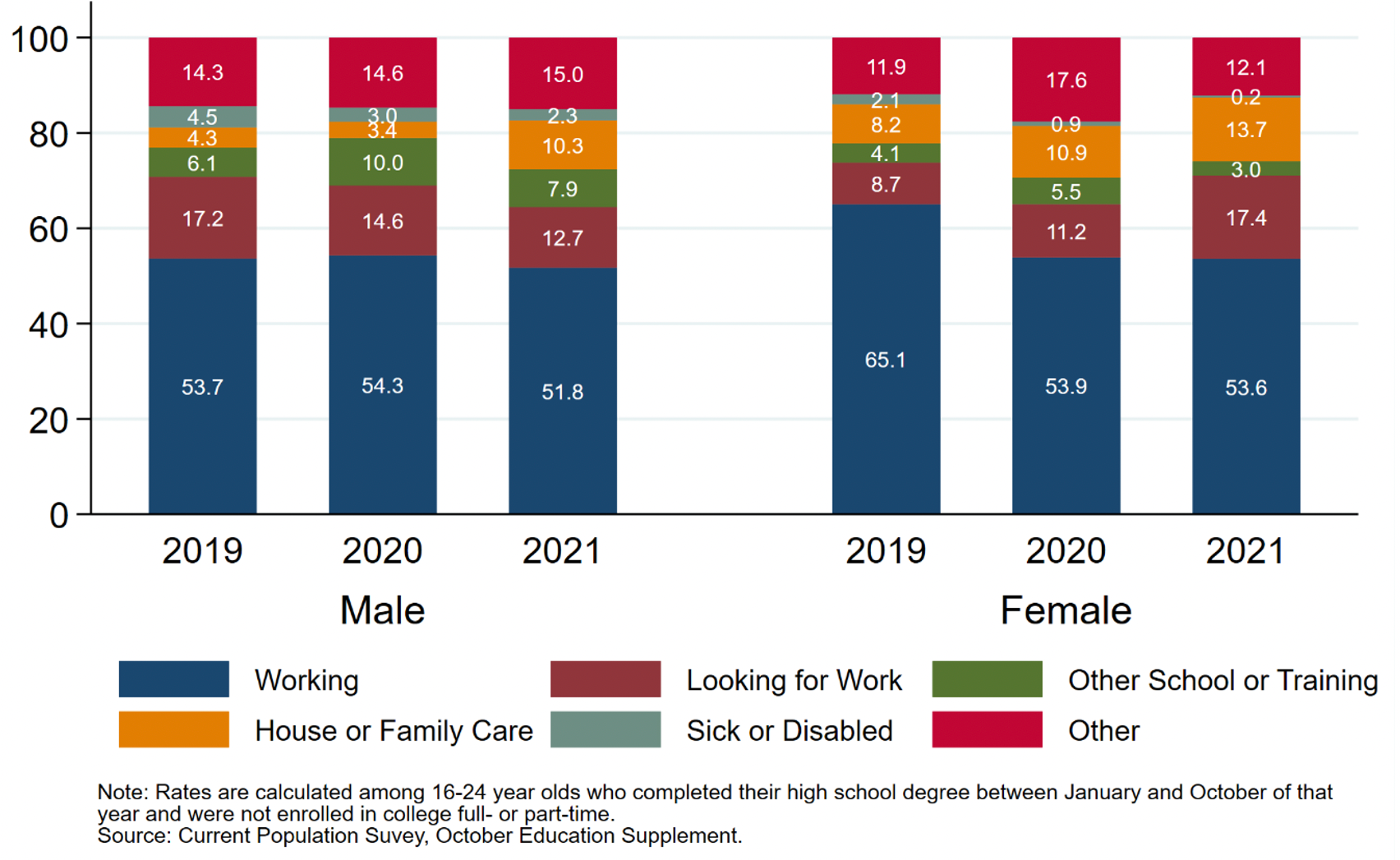

- House or family care was a large factor keeping younger men and out of the labor force, particularly in 2021. In 2021, 10.3% of men out of high school not in college cited “taking care of house or family” as the reason they were out of the labor force, compared to 4.5% in 2019. There was also an increase in the share of female non-college enrollees who cited this factor: 13.7% of women cited caregiving responsibilities as the reason they were out of the labor force in 2021, compared to 8.2% in .

Figure 2. Primary Activity of Recent High School Graduates Not in College

THE BOTTOM LINE

The decline in college enrollment rates accelerated sharply during the pandemic and was particularly large among men putting off college right after high school. These graduates did not enter the labor force, but rather many college plans were disrupted by COVID-related caregiving needs. As the individual economic returns to a college degree remain as high as they have ever been and as the business needs for a skilled workforce continue to grow, it is vital to ensure these graduates and future cohorts return to the college pipeline.