Technological Disruption in the US Labor Market

DAVID DEMING, CHRISTOPHER ONG, LAWRENCE H. SUMMERS

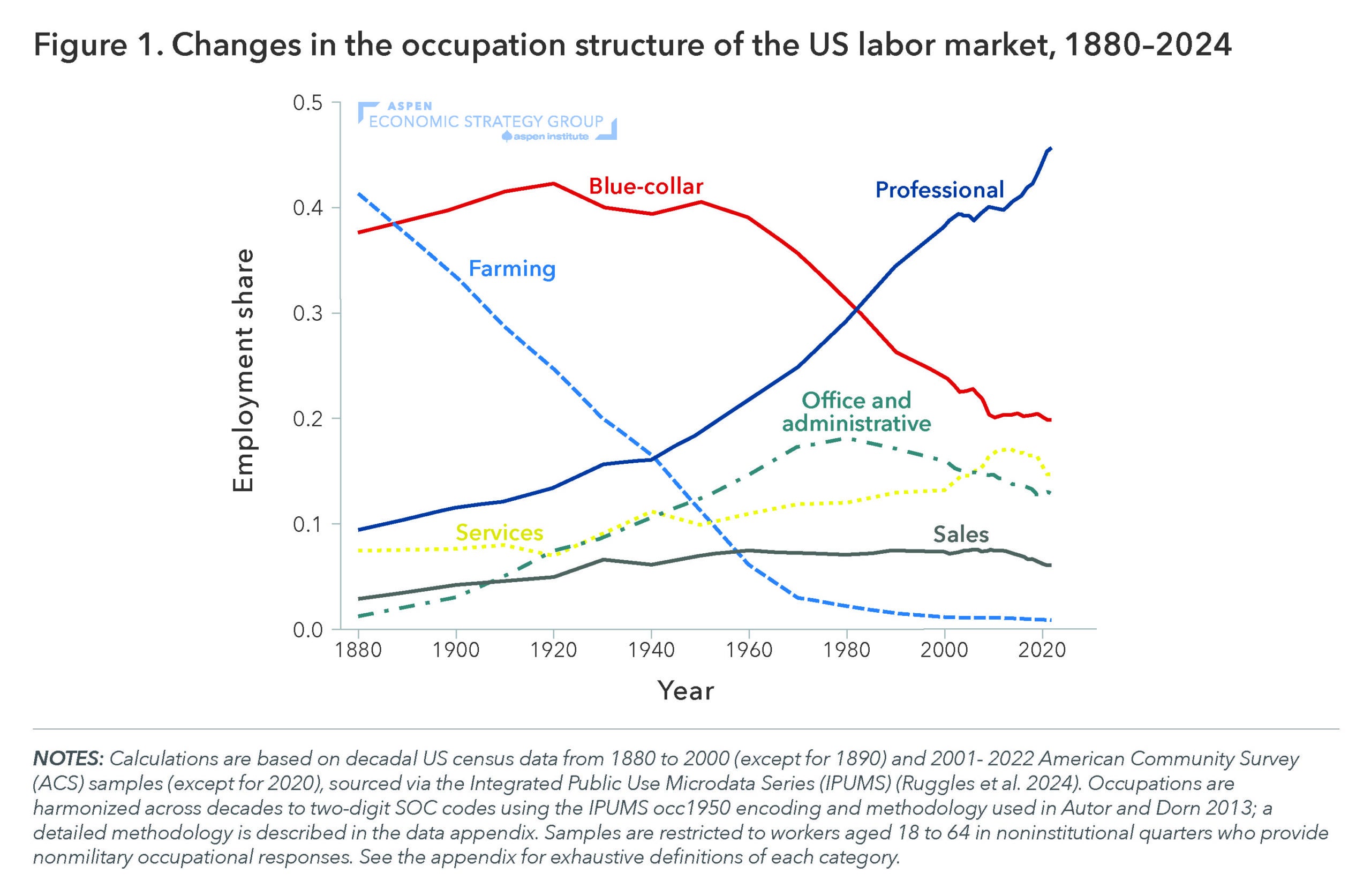

This paper explores past episodes of technological disruption in the US labor market, with the goal of learning lessons about the likely future impact of artificial intelligence (AI). The authors measure changes in the structure of the US labor market going back over a century in two ways. First, they examine the relative frequencies of occupations from 1880-2020. Over that period, the structure of the US labor market underwent two large shifts:

- From 1880 to 1960, workers moved out of agriculture jobs. In 1880, 41 percent of all workers in the US economy were employed as farmers or farm laborers. This share fell consistently by 4 percentage points per decade, and by 1960 only 6 percent of US employment was in agriculture.

- From 1960 to 1980, jobs moved from the factory to the office. The share of workers employed in blue-collar jobs like manual labor, construction, production and manufacturing, transportation, and maintenance and repair remained relatively constant at 40 percent from 1880 to 1960, then fell ten percentage points by 1980. It has experienced a slower decline since, reaching 20 percent by 2010.

They also find that the pace of change, as measured by occupational churn, has slowed over time: the years spanning 1990 to 2017 were less disruptive than any prior period we measure, going back to 1880. This comparative decline is not because the job market is stable today but rather because past changes were so profound.

These changes were caused by general-purpose technologies (GPTs), like steam power and electricity, which dramatically disrupted the twentieth-century labor market over the course of several decades. The authors argue that AI could be a GPT on the scale of prior disruptive innovations and suggest that there are two patterns in the data that might indicate that AI is leading to labor market disruptions along the lines of past GPTs. First, increased investment in new technologies and a J-curve pattern of productivity growth in AI-exposed sectors. Second, large but steady declines in employment share for AI-exposed jobs, especially jobs in sectors where consumers don’t increase consumption with rising income. They present early evidence of such signs in four stylized facts:

- The labor market is no longer polarizing— employment in low- and middle-paid occupations has declined, while highly paid employment has grown.

- Employment growth has stalled in low-paid service jobs.

- The share of employment in STEM jobs has increased by more than 50 percent since 2010, fueled by growth in software and computer-related occupations.

- Retail sales employment has declined by 25 percent in the last decade, likely because of technological improvements in online retail.

The authors conclude that, with respect to white collar-jobs, AI will contribute to the ongoing decline in back-office administrative jobs and rise in management and business operations occupations. As AI technology improves, innovations like pricing algorithms and automated scheduling may lead to declining employment in sales and administrative-support occupations. On the other hand, while AI helps with certain tasks of professional and managerial workers, the demand for good ideas and cogent analysis of complex counterfactual thought experiments may be nearly unlimited. In this way, at least in the near term, AI is more likely to ratchet up firms’ expectations of knowledge workers than it is to replace them.

Suggested Citation: Deming, David, Christopher Ong, and Lawrence H. Summers. 2024. “Technological Disruption in the US Labor Market” In Strengthening America’s Economic Dynamism, edited by Melissa S. Kearney and Luke Pardue. Washington, DC: Aspen Institute. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13973975.